Syria’s Military Intelligence Division:Structure & Instruments of Repression

Summary

- This study offers an in-depth reading of the Military Intelligence Division as one of the most influential pillars in the Assad regime’s architecture, rather than as a mere security agency within a broader apparatus. It begins from a central question: what was the Division’s institutional structure, and what were its multiple, branching roles and powers?

- The study briefly traces the historical formation of the Military Intelligence Division, from its transition from the “Second Bureau” into the institutional form established in 1969, and then through its transformation—with the rise of the Baath Party and the consolidation of Assad family rule—into something akin to a “state within the state”.

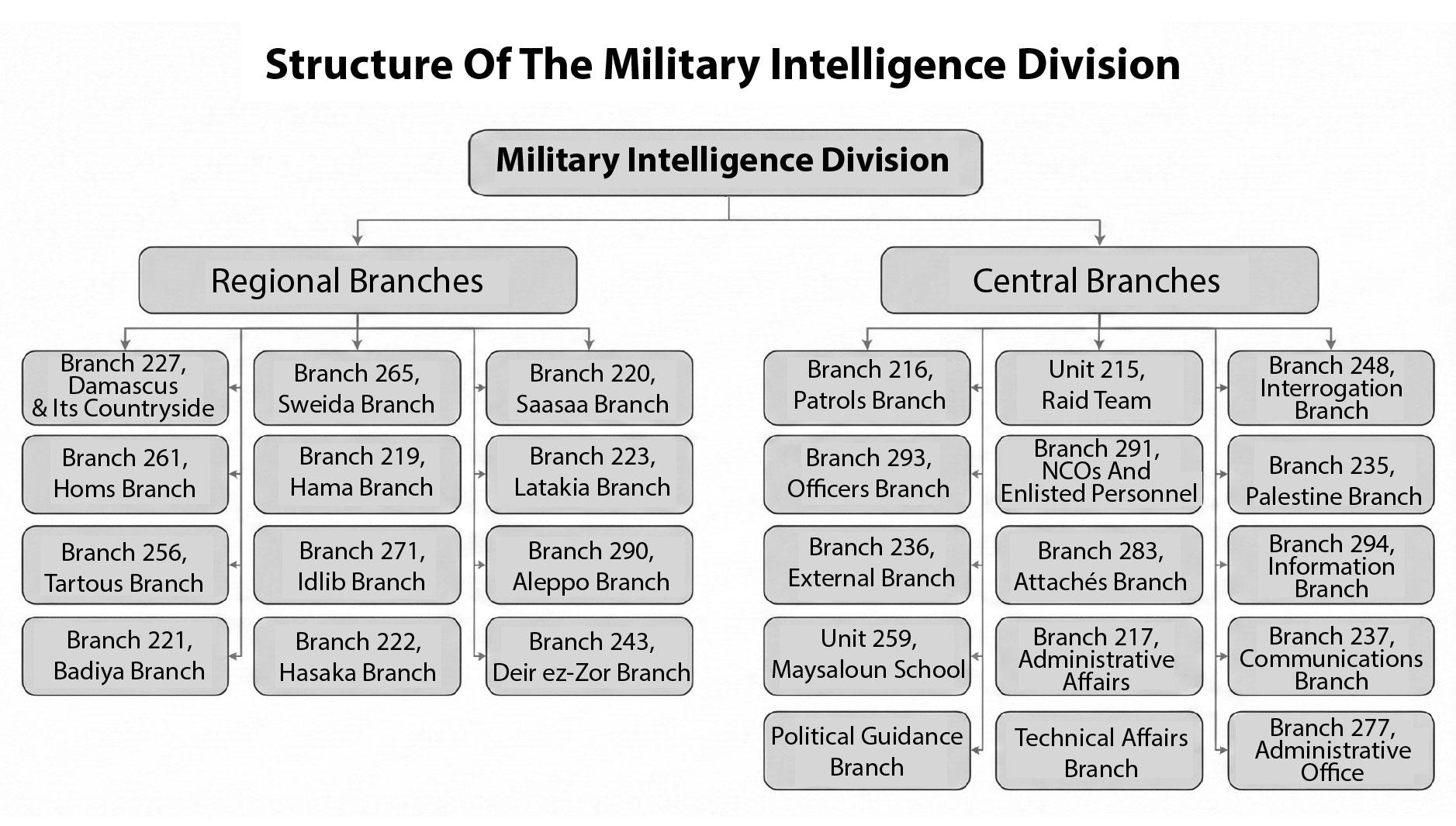

- It breaks down the Division’s organizational structure into two main tiers: the central branches in Damascus and the regional branches in the provinces. The central branches formed a network for decision-making, planning, and centralized management that controlled officers’ files, military unit movements, the cycle of detention, interrogation, and referral, Palestinian and foreign files, and the agency’s internal capacity-building. The 12 regional branches spread across the provinces represented the Division’s direct executive arm within Syrian territory.

- The study shows how the functions of the Division went far beyond conventional military intelligence to the management of a comprehensive system of repression. Over time, the Division accumulated an array of tools: sweeping surveillance of the army and society through wiretapping and networks of informants; arbitrary arrests based on wanted lists and denunciations; preventive arrests to strangle protest before it began; detention in conditions that led to loss of life; systematic torture; and the organized use of military courts, terrorism courts, and field courts to channel arbitrary detention and torture into a “legal” pathway ending in military prisons or execution.

- The study argues that dismantling the legacy of the Military Intelligence Division in a future Syria cannot be reduced to renaming branches; instead it requires a layered approach that combines transitional justice, security sector reform, and a redefinition of the role of military intelligence within a new social contract. Restricting the agency’s mandate strictly to the military realm, opening its archives to victims of detention and enforced disappearance, and rewriting public memory around military intelligence prisons are all essential conditions for preventing the re-emergence of the “security state” in a new guise.

Introduction

The Military Intelligence Division formed a cornerstone in the machinery of repression and subjugation in the Syrian state from the post-independence period until the fall of the Assad regime at the end of 2024. Its most decisive role, however, accompanied the rise of the Baath Party in 1963 and the entrenchment of Assad family rule over the following five decades. In its tasks and functions, the Division moved beyond a narrowly military remit, recasting itself as a comprehensive instrument of security, political, and social control armed with extraordinary, supra-legal powers and shielded from any oversight or accountability. The expansion of this institution had a decisive impact in entrenching the logic of the police-security state in Assad’s Syria and in shaping a public consciousness in which the intelligence services, rather than courts or laws, became the real arbiter of individual lives and fates.

The Military Intelligence Division is one of Syria’s oldest intelligence services, established in its present form in 1969. Before that, it was known as the Military Intelligence Directorate(1) or the Second Bureau (Deuxième Bureau), whose roots dated back to the French Mandate.(2) In the decades that followed, the Military Intelligence Division, also known as Military Security, became one of the Assad regime’s principal intelligence agencies, alongside the Air Force Intelligence Directorate, the General Intelligence Directorate (State Security), and the Political Security Division.

Although the Military Intelligence Division was formally subordinate to the General Command and thus to the Ministry of Defense, it played a pivotal role in selecting the Chief of Staff and the Minister of Defense, and it was closely tied to the National Security Office. The Division carried out a broad set of tasks: collecting military intelligence, securing the borders, monitoring military communications, and tracking the behavior of military personnel to detect internal security threats; it was also responsible for overseeing military detention facilities.(3)

Its remit, however, was never confined to the military sphere. The Division participated extensively in arrest, detention, and enforced disappearance, and it emerged as the security body that intruded most deeply into civilians’ lives. It was the authority responsible for issuing the largest number of arrest warrants against Syrians,(4) in addition to its well-known dominance within the army itself. (5)

Against this backdrop, the study examines the Military Intelligence Division itself as one of the central pillars of Syria’s security system, with particular attention to the period 2011–2024. It seeks to dissect the Division’s institutional structure, the mandates of its central and regional branches, and the patterns of overlap with other security and judicial bodies, treating the Division as a core mechanism through which violence and domination were continually reproduced.

The importance of this study lies in the way it casts the Military Intelligence Division as a fully fledged institutional actor, not merely a “security agency” within a broader “national security” framework. It seeks to show how the Division became a central node in the web of grave violations documented during the Syrian Revolution, how its structure and operating methods helped produce systematic torture and enforced disappearance, and how it controlled the trajectories of hundreds of thousands of prisoners. The study also aims to provide an entry point for supporting criminal and administrative accountability efforts targeting the Division’s leaders, branch heads, and personnel—both military and civilian contractors—and for informing mechanisms tasked with searching for the missing and forcibly disappeared. In doing so, it contributes to a deeper understanding of the Division, alongside an understanding of the referral pathways managed by military intelligence branches throughout the years of the uprising, a topic addressed in an earlier study entitled “Referring Civilians to Military Prisons During the Syrian Revolution: Procedures, Pathways, & Judicial Gateways (Sednaya Prison as a Case Study)”(6).

Building on this, the study’s central question can be summarized as follows: what were the roles and tasks of the Military Intelligence Division, what was its organizational architecture, and what tools of repression allowed it to penetrate Syrian civilian and military society and to shape the pathways of detention, interrogation, and judicial referral?

Within this composite question, a set of sub-questions emerges, the answers to which form the backbone and structure of the study:

- What were the roles, tasks, and limits of the Military Intelligence Division’s powers?

- What was the organizational structure of the Military Intelligence Division (central branches, regional branches), and what were their administrative subordination lines, mandates, and powers?

- What were the Division’s instruments of repression and control (monitoring the army and society, arrest, interrogation, judicial referral), and how were they used in practice to manage prisoners’ security files?

To answer these questions, the study relies on two principal types of data source—primary and secondary—used in a complementary way to understand and analyze the Division under examination. They can be summarized as follows:

First, leaked security-agency documents: this category includes hundreds of records issued by the Military Intelligence Division and its various branches, along with referral and arrest files cited in analytical reports, and older documents dating back to the 1970s as well as more recent materials that surfaced after the fall of the Assad regime, all of which show the Division’s position within the architecture of power under Assad father and son.

Second, interviews: conducted with a range of actors directly connected to the subject of this study, among them a former officer who defected from the Military Intelligence Division, and human rights activists who worked on documenting violations.

Third, human rights and UN studies, papers, and reports: produced by local and international bodies that examined the security agencies file in Syria, with particular emphasis on the Military Intelligence Division, or focused on patterns of arrest, torture, enforced disappearance, and the routes of referral to military prisons and courts.

I. Roles, Tasks, & Limits of the Military Intelligence Division’s Powers

In the security and political architecture that Hafez al-Assad entrenched in the early 1970s, the Military Intelligence Division emerged as one of the regime’s most formidable and influential instruments of rule. Although it was formally defined as an agency concerned with the military institution, it soon turned into a comprehensive apparatus of coercion in which security and politics intersected and personal loyalty was bound up with the surveillance of both army and society. The Division reported directly to Assad, bypassing the formal party hierarchy, and functioned as a parallel center of decision-making whose influence exceeded that of the Baath Party and state institutions.

The Division’s role was not limited to internal surveillance of the army in general and Sunni officers in particular—tracking their movements and producing periodic loyalty reports that preempted any possibility of an anti-regime current forming within the military; it also extended to monitoring political opponents and following civil opposition movements. The Baath Party itself had no meaningful influence over the Division’s work, even though most of the Division’s officers and personnel were formally enrolled in the party and internal party cells existed within it. In practice, the Division operated beyond party oversight and accountability mechanisms, obeying instructions from the presidential palace and working under the supervision of the National Security Office; it became, in effect, a state within the state and the core of the security apparatus that was later handed down into the era of Assad’s son with only cosmetic adjustments that left this dominance untouched.

With the outbreak of the Syrian uprising in March 2011, the Division’s roles multiplied and its powers expanded; it moved from monitoring public life to leading a central part of the security confrontation with the popular movement. It played a direct role in repressing peaceful demonstrations and organizing mass arrest campaigns, especially in areas with a strong military presence or close geographic proximity to the capital, as well as across the provinces through regional branches, sections, and field detachments spread throughout the country. These branches and detachments turned into initial detention and interrogation centers where torture and cruel treatment were practiced; survivors’ files were then referred to the military judiciary and military field courts, before tens of thousands were transferred to military prisons—foremost among them Sednaya Prison—on the basis of decisions issued by branch officers or recommendations addressed to judges in those courts.

The Military Intelligence Division took on a vast range of functions that went far beyond the technical profile usually associated with military intelligence agencies. Within the army, it effectively controlled officers’ transfer and promotion paths in the armed forces, in addition to monitoring their behavior and assessing their loyalty.(7) The head of the Division was a member of the Military Defense Council within the armed forces,(8) and also sat on the Officers Committee in the army.(9)

It also monitored the movement, composition, readiness, and loyalty of military units, and maintained records of bases, units, and artillery. No major deployment could take place without its approval and coordination, alongside its oversight of the military police attached to combat formations.(10)

The Division likewise carried out extensive technical and intelligence tasks through specialized branches, most notably the Signals Branch and the Communications Branch. The Signals Branch was responsible for monitoring and encrypting radio communications within the army and security services and for conducting technical surveys and wiretapping, while the Communications Branch monitored all wired and wireless lines in the armed forces and supervised the implementation of military communications projects across the country. The Division also tracked internet activity and monitored the virtual space, intervening to block websites or hack online activities, and followed local and international media and digital platforms, using them to produce security assessments for the leadership. At the operational level, its branches and field detachments carried out raids, arrests, abductions, and assassinations, and ran places of detention under its authority where torture in its various forms was practiced.(11)

The Military Intelligence Division wielded considerable power over the management of Sednaya Prison. It supervised the White Building in Sednaya Prison, and no one could enter that building or visit any prisoner held there without permission from the military police, which was granted only after prior security clearance from the Division. In addition, the Division provided protection for the prison at the middle gate through a detachment subordinate to Branch 227 (the Region Branch), whose role was not limited to guarding; it also monitored the prison from a security perspective, dealt with the families of security prisoners during visits, and arrested any visitor deemed to have violated instructions or prison security. The Division oversaw the appointment of officers to the prison and their transfer in and out; it received specialized periodic reports, which were sent on to various central branches depending on their subject matter; and the presence of a Division officer was mandatory on any committee tasked with carrying out death sentences.(12)

In conjunction with the other services, the Division’s mandate and powers extended beyond the conventional model of military intelligence to the management of a broad internal system of repression. Syria’s four intelligence agencies—foremost among them the Military Intelligence Division—had de facto, open-ended authority to conduct arrests, searches, interrogations, and detention; they operated with a high degree of autonomy and reported directly to the head of the regime, and all of them were implicated in the killing of unarmed demonstrators, arbitrary detention, and torture. Before 2011, their primary role lay in monitoring citizens through a network of informants and officers embedded in every sector of public life; during the uprising, this role expanded to encompass leadership of field repression operations, accompanying military campaigns, and providing the security cover for shooting at demonstrators, mass arrests, and the transfer of prisoners to interrogation centers and military prisons.(13)

In addition, the Division carried out functions with an external or specialized dimension that went beyond internal army security. Through Branch 235, it handled the Palestinian file inside and outside Syria, monitored Palestinian organizations and sought to infiltrate and steer them, and kept Palestinian refugees under surveillance, before the branch’s mandate expanded to pursuing Islamic organizations and branding wide swaths of political and religious activity as a so-called security threat. Branch 220 in Saasaa, responsible for the Quneitra area, handled intelligence affairs in the occupied Golan, monitored United Nations forces, and coordinated with armed Palestinian factions. The Division also supervised the Military Intelligence School, which was responsible for training its cadres in security and military sciences—making internal capacity-building a structural part of its mission and reinforcing the continuity of its role in enforcing security over society and the army.(14)

It is impossible to grasp the scale of the grave violations committed by the security services without unpacking the institutional structure that enabled them, and the Military Intelligence Division in particular. Massacres inside detention facilities, the steady flow of referrals to military and field courts, and then to Sednaya Prison, were not isolated decisions or individual excesses, but the product of a closed security architecture that enjoyed functional and administrative autonomy and was run through internal mechanisms that did not answer to any principle of the rule of law. This structure allowed the Division to design integrated trajectories of repression that began with arrest, interrogation, and torture and did not end with physical liquidation; they extended to controlling the military institution itself and determining officers’ promotion and disciplinary paths, thereby tightening and perpetuating the security circle.

II. Structure Of The Military Intelligence Division

The Military Intelligence Division used a three-digit numerical reference system to designate its branches, whether central branches in Damascus or regional branches in the provinces. Among its most prominent central branches were: Branch 248 (the Interrogation Branch), Branch 235 (the Palestine Branch), Branch 215 (the Raid Team), Branch 227 (the Damascus Region Branch), and Branch 290 (the Aleppo Branch). In addition, there were sub-branches in various cities,(15) as well as hundreds of checkpoints and field detachments staffed by Division personnel, particularly after 2011.(16) Over the following years, the Division also established a large number of loyal militias. These militias performed the same roles as Division personnel, especially in carrying out arrests and violations.(17)

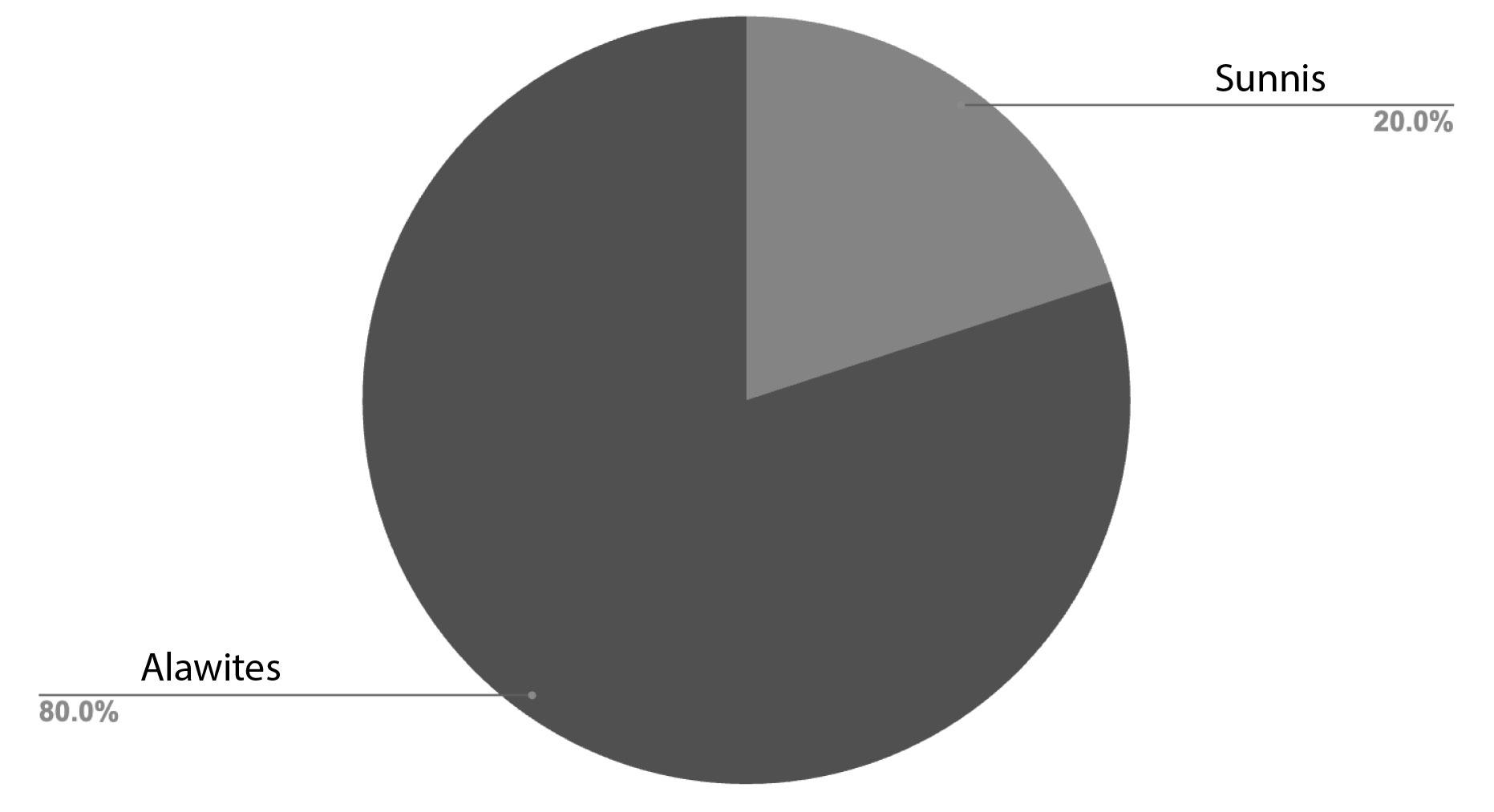

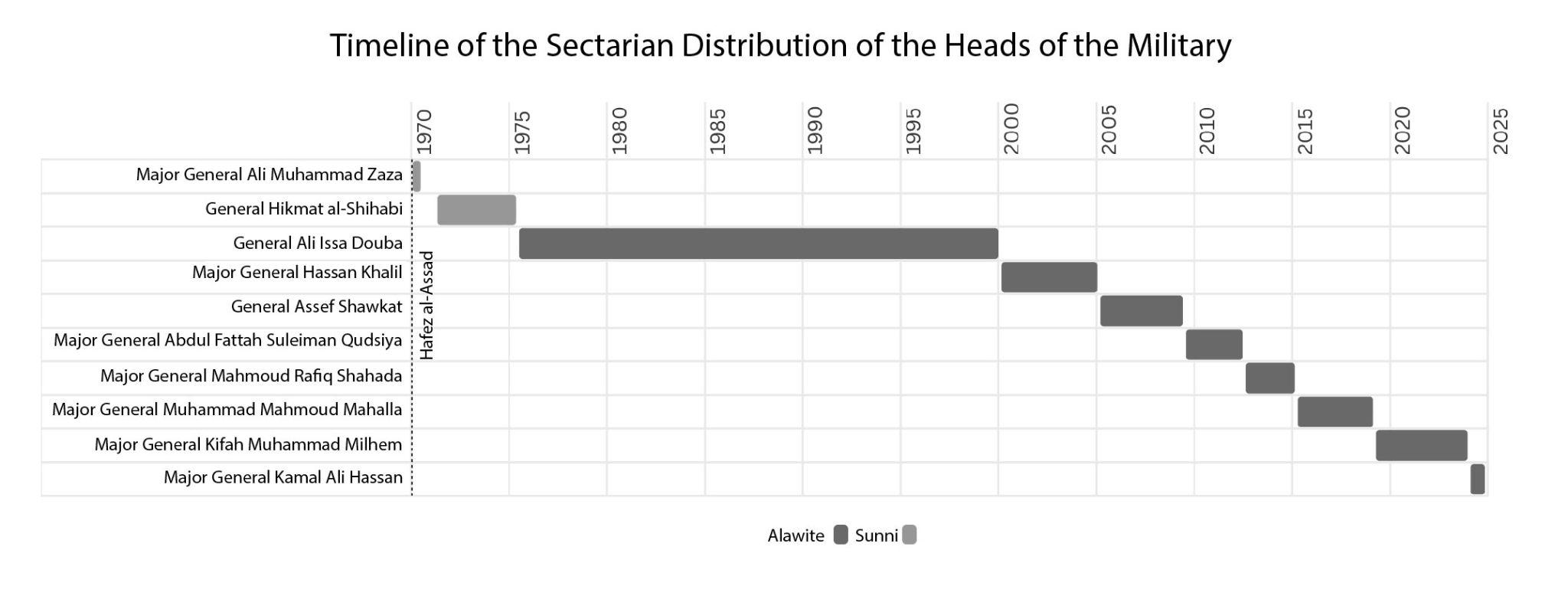

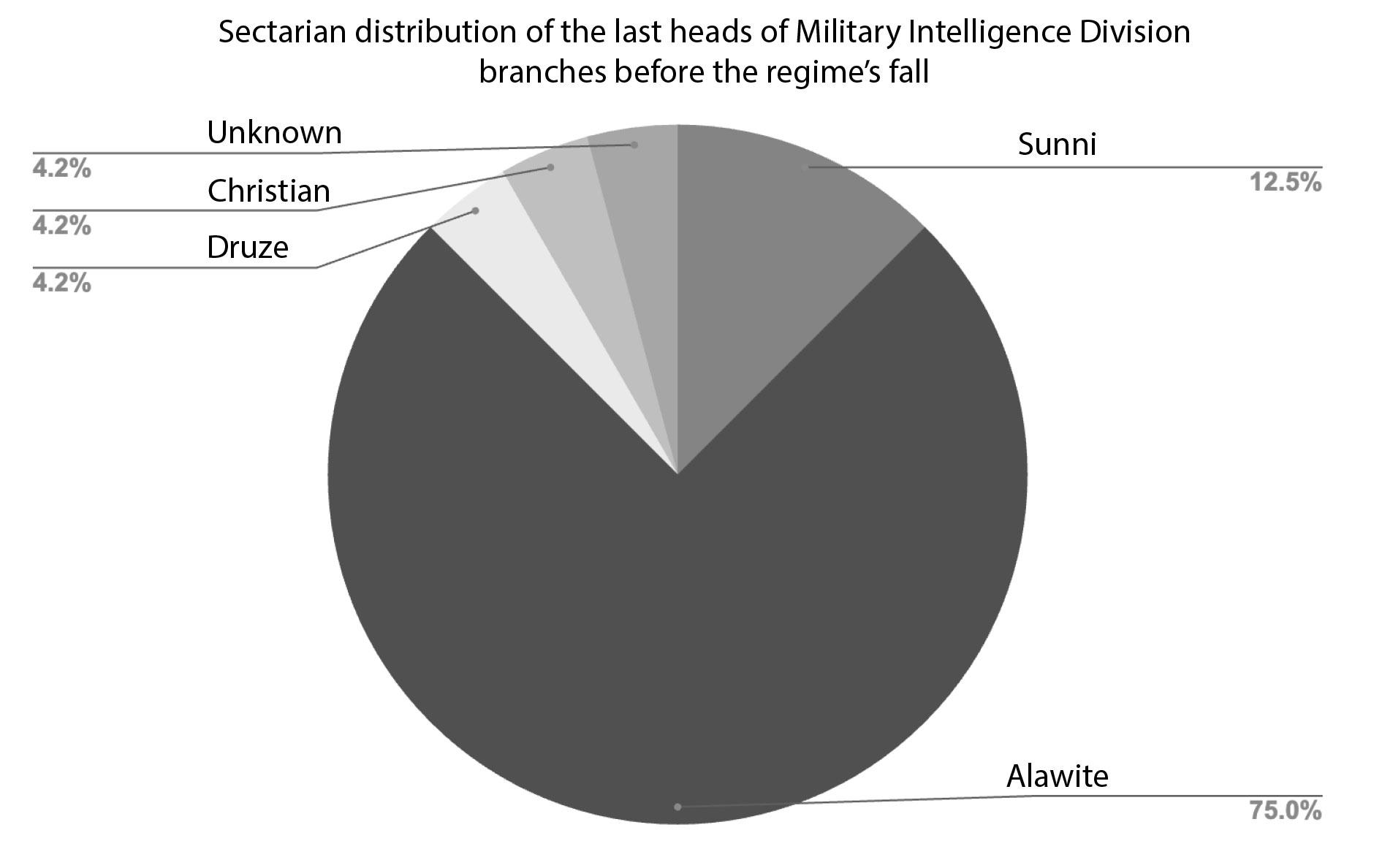

The Division was headed by a major general appointed by the General Commander of the Army and Armed Forces. The major general in charge was assisted by a deputy who also held the rank of major general. Those appointed to lead the Division were typically officers who had previously served in key central branches such as Branch 235, Branch 293, Branch 294, or Branch 227. The Division was built around a cohesive, elite security and sectarian core; from 1974 until the regime’s collapse, it was led exclusively by officers from the Alawite community.(18) This is crucial because the Division was responsible for monitoring the army, its loyalty, and its performance; it served as the army’s safety valve as the largest and most powerful force protecting the Assad regime. As a result, the Division became highly sectarian, both at the level of its commanders and the heads of its subordinate branches.

Figure (1): Sectarian distribution of heads of the Military Intelligence Division since 1965

Figure (2): Timeline of the sectarian distribution of Heads of Military Intelligence Division branches since 1965

Figure (2): Timeline of the sectarian distribution of Heads of Military Intelligence Division branches since 1965

Figure (3): Sectarian distribution of the last Heads of Military Intelligence Division branches before the regime’s fall

Figure (3): Sectarian distribution of the last Heads of Military Intelligence Division branches before the regime’s fall

A- Central Branches

The Military Intelligence Division’s central branches were of particular importance; they formed the core of the apparatus and the arena in which general directives were drafted, and from which the broadest security files touching the state, the army, and society were managed. They set priorities for intelligence work, coordinated the Division’s relationship with other security and judicial bodies, oversaw the system of arrest, interrogation, and judicial referral, and monitored the loyalty of military formations.

Against this backdrop, this section sets out the Division’s most prominent central branches, the mandate of each, and its place in the overall structure, in order to untangle the interconnected roles that, taken together, produced a highly centralized and far-reaching security apparatus.

Branch 248, the Interrogation Branch

Branch 248 was the Division’s central interrogation branch. It was located alongside other security branches in the security quarter of the Kafr Sousa neighborhood, southwest Damascus. The branch handled interrogations of detainees held on a broad spectrum of charges, including offenses against internal and external state security; participation in political organizations and hostile clandestine associations of all kinds; cases of demonstrations, rioting, insubordination, and rebellion; smuggling in all its forms; unlawful possession of and trafficking in weapons and ammunition; crimes against persons, public administration, and property; counterfeiting currency and forgery; drug use; illegal excavation for and trafficking in antiquities; participation in criminal gangs without a political character; offenses that obstructed the course of justice; identity-fraud cases involving evasion of civil registration and people whose nationality status was considered a security concern; in addition to military offenses of all kinds and crimes deemed contrary to public morals.(19)

The branch also reviewed and scrutinized all investigation files referred from other Division branches, issued legal opinions on them, determined how to use them, and reported observations to the Division’s leadership so they could be addressed procedurally. It provided legal advice on matters of concern to the Division, and it prepared memoranda intended to prevent Division personnel from being prosecuted in the event of armed clashes. It monitored the status of Division personnel before judicial bodies. It also handled the procedures for referring detainees whom the central branches had decided to send to the Military Field Court.

Branch 248 also supplied the National Security Office with daily reports on people detained by the Division’s branches, specifying those referred on to other security or judicial bodies and those who had died in custody. It answered inquiries from the National Security Office and other security agencies about the status of detainees and wanted persons whose cases fell under the Division’s remit. In addition to these tasks, the branch, when needed, backed up other Division branches in pursuing “armed terrorist groups,” seconding personnel to other branches and to newly formed security committees. Internally, it comprised a number of interrogation sections (political, smuggling, criminal, disciplinary, follow-up and prison) and several offices dealing with the matters listed above according to their specialization. The branch also housed three prisons: the main prison, the Evaluation Unit prison, and the women’s prison.

Unit 215, the Raid Team

Unit 215, also known as Branch 215, was one of the Military Intelligence Division’s most prominent arms. It was defined by its dual nature as both an interrogation and documentation body, and a combat unit specialized in raids and arrests in Damascus and its suburbs. Official documents refer to it variously as Unit 215 or as the Raid Team, a shifting nomenclature that reflected its movement between administrative and intelligence work on the one hand and field operations on the other.(20)

Its base stood in Kafr Sousa, in the Military Intelligence Division’s security quarter, alongside branches such as 227, 248, and 293, which made it a central hub in the capital’s cycle of detention and disappearance. It was tied directly to Military Hospital 601, through which victims’ bodies formally passed before their deaths were recorded under fabricated medical causes, after which their files were sent on administratively to Branch 248 to be closed. In this way, an administrative architecture of killing emerged, linking branches, hospitals, and the military police.

Branch 215 functioned as an integrated system that turned arrest, interrogation, and liquidation into documented office procedures. It was one of the Division’s largest units in terms of manpower and tasks; it had around 2,000 personnel distributed across nine main sections and five combat teams, all of which worked to regulate the cycle of violence from the moment of arrest through disappearance or killing.

Branch 215 had a wide institutional structure that brought together administrative, security, and technical sections which collectively served as the operating center for the cycle of detention and surveillance. At its core was the Administrative Office (Diwan), the administrative engine that managed personnel files, correspondence, archiving, and training. Alongside that, the Information Section acted as an analytical hub that gathered data and entered it into digital archiving systems. Working next to those two, the Counterterrorism Section was the most active field arm, encompassing the interrogation offices, operations offices, and the prison detachment, and forming the axis around which detention and liquidation revolved. This structure was complemented by the Technical Section, responsible for communications, networks, and surveillance systems; the Administrative Affairs Section, which provided services and logistics in the branch; the Investigation Section, which managed detailed interrogations; the Engineering Section, which specialized in detecting explosives and carrying out preventive surveys; and the Technical Affairs Section, which supervised technical operating equipment.

At the field level, the five teams formed the branch’s executive arm: the Raid Team, which carried out raids and arrests in Damascus and its countryside; the Checkpoints and Guard Team, responsible for checkpoints and for securing facilities; the Women’s Volunteer Team, which handled cases involving women; the Services and Logistics Support Team, which managed transport, supplies, and warehouses; and the Engineering and Field Survey Team, tasked with detecting explosives and suspicious objects. Through this tight coupling of office-based sections and field teams, Unit 215 operated as an integrated security and military apparatus that combined administration, interrogation, surveillance, and execution.

Branch 216, the Patrols Branch

Branch 216, also known as the Patrols Branch, was located in the Qazzaz area on the road to Damascus International Airport. It was classified among the Military Intelligence Division’s central branches.

Alongside Unit 215, Branch 216 was the Military Intelligence Division’s field-executive arm; it implemented orders issued by the Division’s leadership and central branches regarding security operations on the ground. In practice, it carried out raids, arrests, and the apprehension of wanted persons, pursued targets that required the direct presence of security officers and personnel, and served as a conduit between security decision-making rooms and the field space of neighborhoods, cities, and towns.(21)

Documents show that this monitoring was not random but methodical and divided by geography and function. For example, surveillance of the Saudi embassy fell under the responsibility of the western Mezzeh sector, through coordination between Unit 215 and Branch 216 (southern sector), while final information was passed to Branch 294 for centralized review. This administrative division shows that the regime ran its external security work according to the same logic it applied in detention centers: a rigid hierarchy, daily reporting, and meticulous central archiving.(22)

In terms of its record of violations, Branch 216 became one of the most emblematic symbols of repression in the Syrian security apparatus. Its name is associated with detention centers where systematic torture and deaths under torture were documented, especially after 2011. Branch 216 can be thought of as a microcosm of the repressive system exercised by the Military Intelligence Division. It was a field-executive arm that led raids and arrests outside, and a detention and interrogation center that relied on systematic torture inside. It embodies violations for which survivors and relatives of victims demand accountability in any future transitional justice process.

Branch 235, the Palestine Branch

Branch 235, known as the Palestine Branch, was located in the Qazzaz neighborhood on the road to Damascus International Airport. It lay in a security complex that housed several other facilities, including Patrols Branch 216, which was almost adjacent to it. The branch occupied a large building with seven floors above ground and three floors below ground designated for detention and interrogation.

Branch 235 was one of the Military Intelligence Division’s oldest and most important branches; it was created to serve as the regime’s primary arm for managing the Palestinian file. It was tasked with monitoring Palestinian organizations and Palestinian refugees in Syria. Through a special unit known as the Fedayeen Control Unit, which handled the affairs of the Palestine Liberation Army and the armed factions linked to it, the branch coordinated security and political relations with factions authorized to operate in the country—such as Fatah, the as-Saika movement, the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine, and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. Over time, it grew into a fully fledged intelligence directorate active on both the domestic and external fronts.(23)

The Palestine Branch had a highly complex structure commensurate with the scale of its tasks. The upper building was divided into floors specializing in specific issues—for example, files on Islamists, weapons and forgery cases, political files concerning dissenters, the Palestinian issue, and cases labeled terrorism. The three underground floors were used as isolation cells, group cells, and interrogation rooms.

Following the outbreak of the Syrian Revolution in 2011, the branch was assigned a central role in suppressing protest in south Damascus. It pursued defected soldiers and arrested activists and other dissenters, cementing its reputation in the Syrian public consciousness as one of the most brutal security branches. The branch displayed a recurring pattern of grave violations throughout the revolutionary years. At least 520 Palestinian prisoners were documented as having been killed under torture between 2011 and 2018—a partial figure that reflects only a segment of the victims.(24) Available information indicates that 2,710 prisoners died in the Palestine Branch between 2011 and 2020.(25)

Branch 291, the NCOs and Enlisted Personnel Branch

Branch 291—known by several names, including the NCOs and Enlisted Personnel Branch and, in some accounts, the Forces Security Branch—was one of the Military Intelligence Division’s central branches. Some also referred to it as the Headquarters or Administrative Branch, but its core mandate was to deal with NCOs and enlisted personnel. This involved monitoring them, ensuring their loyalty to the regime whether they served in security branches or military units, and interrogating them whenever suspicions arose, in addition to carrying out arrests and interrogations.(26) In a pattern similar to that of Branch 293, security officers and NCOs in each unit were linked to Branch 294.

The branch played an internal oversight role over the Division’s officers and personnel by tracking professional conduct and loyalties and submitting periodic evaluation reports that were used in decisions on promotion, transfer, and dismissal. These reports were sent directly to the Division leadership and, in some cases, straight to the presidency.(27)

The branch’s work was not confined to military personnel; its remit extended to civilians as well. It participated intensively in arrest and interrogation operations targeting civilians, and incidents of arrest and torture were documented in the branch, in keeping with patterns seen across other Military Intelligence Division branches.

Branch 293, the Officers Branch

Branch 293—known as the Officers Affairs Branch or the Officers Security Branch—was one of the Division’s most important central arms and among the most influential. Its headquarters were located in the security compound in the Kafr Sousa neighborhood of Damascus.

Functionally, Branch 293 was responsible for monitoring officers in the Syrian army across the ranks and formations, gathering information on their movements, conduct, and affiliations, and compiling detailed security files on each officer. The regime relied on the branch’s reports when deciding on promotion, transfer, and removal, especially in sensitive posts, such that security loyalty became the decisive criterion shaping an officer’s career. The branch reported directly to the head of the Military Intelligence Division, while its commander enjoyed a direct line to the president in major cases involving army officers. This made Branch 293, in effect, the internal oversight body for the armed forces and a principal tool for ensuring the loyalty of the military leadership.(28) Security officers of all military units reported to this branch and submitted security reports on officers and on conditions in the units.

Branch 293 received security information from other branches such as 248, 235, 291 and 227, particularly when army officers were detained or interrogated. Although its core mandate was to keep officers in check internally, beyond that formal role the branch was directly involved in arrest, torture, and enforced disappearance, especially in cases involving officers and military personnel suspected of disloyalty or those who had defected and later entered into reconciliation arrangements.

Branch 294, the Information Branch

Branch 294 was one of the Military Intelligence Division’s central branches, with a remit that extended across the entire army. It was sometimes referred to as the Forces Security Branch because of the way its work intersected with security branches and army units.(29) Its mandate revolved around monitoring all army formations by tracking the movements of divisions, brigades, and units and gauging their discipline and loyalty to the regime leadership. To that end, the branch kept detailed files on bases and formations, covering their combat readiness, degree of preparedness, manpower composition, and assessed level of loyalty.(30)

The branch wielded broad practical authority over the movement of the armed forces as a whole. No large military force was allowed to move between locations without prior coordination with and approval from Branch 294, after which Branch 216, the Patrols Branch, verified the movement on the ground. In effect, Branch 294 granted a “movement authorization” to monitor any unapproved movement or one that might signal rebellion or defection.(31) It also exercised direct oversight over the military police and its units attached to divisions and formations, using this power to control personnel suspected of disloyalty or problematic conduct, including by detaining and punishing them in facilities under its authority or in coordination with other interrogation branches, or by sending them to Sednaya Prison as a final destination.

At the bureaucratic level, Branch 294 acted as a central node for collecting and distributing security information between the Division’s central leadership and its regional branches. It issued periodic security bulletins to Military Intelligence branches in the provinces and received daily reports from them on the status and activity of military units, which it then reworked into situation assessments and directive memos for the Division’s leadership. Documents show that some of the final information produced by surveillance operations carried out by other branches was sent to Branch 294 for centralized review,(32) underscoring the degree of overlap in how security branches operated even within a single apparatus.

Branch 283, the Attachés Branch

Branch 283 was the Attachés Branch within the Military Intelligence Division. Based in Damascus, it was the branch responsible for managing external military relations. Its mandate focused on monitoring embassies and foreign missions in Syria, overseeing the affairs of foreign residents, and coordinating with Syrian military attachés abroad.

Branch 283 functioned as a link between the Military Intelligence Division on the one hand, and Syrian military attachés in various countries on the other. It monitored the movements and communications of diplomats and foreigners, tracked what happened in the vicinity of embassies, and oversaw media and political activity connected to foreign actors.(33)

The branch gathered relevant information by monitoring media outlets and foreign organizations and fed the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the military leadership with periodic reports. Documents indicate that Branch 283 developed a specialized unit dedicated to tracking opposition media abroad during the years of the Syrian Revolution.(34)

Despite its outward-facing mandate, Branch 283 was deeply involved in internal repression. It took part in the torture and killing of hundreds of prisoners. Testimonies by former prisoners and published reports indicate that the branch targeted Syrians returning from abroad or those in contact with international organizations or opposition media outlets, and that its interrogation methods did not differ from those used in other Military Intelligence Division branches. They included severe beatings, electric shocks, and psychological humiliation. Prisoners of the branch were deprived of lawyers and family visits for long periods. These practices placed the base’s detention practices squarely within the pattern of enforced disappearance.(35)

The records reveal an internal structure that made Branch 283 a hub for coordination between military intelligence, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and other security branches on all matters relating to external issues. Documents published previously show direct channels of communication between Branch 283 and Branch 227 (the Damascus Region Branch), as well as security detachments in Syrian embassies—such as the detachment at the Beirut embassy—for exchanging information and transmitting sensitive reports through diplomatic channels. Those documents also point to the existence of a specialized unit in the branch tasked with collecting what was published in the press and media about Syria, classifying and archiving it, and forwarding it in periodic reports, down to compiling personal details on journalists and activists. It is likely that part of this material was translated into foreign languages in the branch itself. Branch 283 operated as the regime’s eye on the outside world and, at the same time, its security extension inside it, blurring the line between external intelligence work and internal repression.(36)

Branch 236, the External Branch

The main headquarters of Branch 236 were located on the outskirts of the Qaboun neighborhood in Damascus, next to the Special Forces Command and the Higher Military Academy. It was a central branch whose core tasks revolved around security operations outside Syria and around issues that went beyond the routine monitoring of the army inside the country, placing it in a position close to that of an external intelligence service within the structure of military intelligence itself.

Branch 236 played a pivotal role in training military intelligence cadres, particularly security officers assigned to armed forces formations. The building consisted of a ground floor and two upper floors. The first upper floor was allocated to training halls, where courses were held for military-security officers and personnel, including courses to prepare security officers for combat units. Later on, some of these tasks were transferred to the National Institute for Security Sciences. The second floor housed officers’ offices, the archive, and personnel records.(37)

Branch 236 also monitored and surveilled Syrian refugees, activists, and opponents residing abroad, collecting information on their political and social activities through networks connected to Syrian embassies and consulates. This role formed part of a broader cross-border surveillance system used by the security services to pursue opponents in exile and to exert pressure on them or on their families in Syria.(38)

In practice, Branch 236 functioned as a technical–intelligence relay between the leadership of the Military Intelligence Division and other specialized branches by receiving and analyzing information related to opposition activity abroad and submitting periodic reports to the leadership on targeted individuals and networks. This involved using diplomatic missions, informant networks, and technical surveillance tools to gather information on opponents and refugees which served decisions on security bans, the blackmail of relatives inside the country, or the activation of security-judicial cases against wanted persons.(39)

Branch 237, the Communications Branch

This was one of the Division’s central branches and was known as the Communications Branch, or the Wireless Branch. It covered all radio and wireless communications inside the Division,(40) from monitoring and technical inspection to intercepting communications. Its core function was to sweep radio frequencies, track wireless calls, and listen in on them, jam them, or otherwise interfere with them.(41) The branch possessed electronic direction-finders used in surveillance and tracking operations.(42)

Several previous reports have described an attempt to merge Branch 237 with a number of other technical security branches under Russian supervision,(43) but that merger never took place. Branch 237 thus remained a stand-alone branch within the formal structure of the Military Intelligence Division, and the Division continued to treat it as an independent branch subordinate to it. Internal documents list it alongside other central branches such as 211, 225, and 294, rather than as a subsection absorbed into another directorate.(44)

Branch 217, Administrative Affairs

Branch 217, or the Administrative Affairs Branch,(45) was another of the Division’s central branches. It was often misidentified as the Sweida Branch, but the Sweida Branch was in fact Branch 265, which had a Daraa Section attached to it. Branch 217 was located in Damascus, in the Kafr Sousa security quarter.

Functionally, Branch 217 appears to have been responsible for the Division’s administrative affairs. One leaked document notes that “food is distributed to detainees according to the daily meal schedule issued by the Directorate of Assignments via Branch 217,” yet the branch’s role went far beyond narrow administrative tasks; it also managed fighter contracts in militias tied to Military Intelligence, including Liwa al-Quds, the Desert Commandos Regiment, and the Fajr Forces militia in Sweida.(46)

Branch 217’s activities also extended to recruiting large numbers of young Syrians—particularly civilians, men from reconciliation areas, and draft evaders—on six-month contracts for Russian forces operating in Syria(47).

Branch 277, Administrative Office (Diwan)

Branch 277 was based in Damascus and was one of the Division’s central branches, but still was not widely known. It was the Administrative Office (Diwan) Branch, also called the Depository Branch, and was known as the 248 Warehouses—a reference to the Interrogation Branch.(48). Branch 277 was tasked with a set of functions related to managing personnel and human resources issues. It monitored performance in the apparatus to prevent gaps, and its assessments played a supporting role in promoting, sidelining, or transferring staff within the Division. The branch also kept the personnel files of all military intelligence officers and staff, including service records, performance reports, and security assessments.(49)

One of the most important tasks associated with Branch 277 was oversight of the mechanism of provisional seizure of the property of Assad regime opponents. The branch had already carried out systematic security campaigns in a number of areas in southern Damascus and the eastern Ghouta, targeting the property of opponents or of individuals whose assets were seized because of their political positions, whether they were living in regime-held areas or abroad.(50)

Like other Military Intelligence Division branches, Branch 277 also carried out arrest and interrogation, ran its own detention facilities, and practiced torture in them, including against children.(51)

Unit 259, Maysaloun School

In the Military Intelligence Division’s structural tables, Unit 259 was defined as the Military Intelligence School, or Maysaloun School.(52) It was located in the Maysaloun/Dimas area to the west of Damascus near the Damascus–Beirut highway, in a closed military compound directly subordinate to the Division.

Unit 259’s primary mission was to train and prepare the Division’s cadres. It received new conscripts attached to military security for basic training cycles, and ran specialized courses for intelligence officers and NCOs in reconnaissance, field security, interrogation methods, and intelligence operations. It also trained members of counterterrorism units, special missions units, and the protective details for senior officials, making it a production hub for the specialized cadres on whom the Division relied for its sensitive operations.

With the outbreak of the Syrian Revolution, Maysaloun School shifted from being a purely training center to a dual-use facility. It was both a school and a secret prison used for holding Syrian, Palestinian, and other prisoners, in line with other security branches under the Military Intelligence Division.(53)

Other Central Branches and Units

The Division also had a Technical Affairs Branch, a Political Guidance Branch, and a medical center subordinate to the Division’s headquarters, along with other offices that answered directly to the Division.(54)

Taken together, the Military Intelligence Division’s central branches were not merely administrative or technical units within the state; they formed the state core through which Syrians’ subjugation was organized and through which they were reduced from citizens to mere “security files”. By accumulating powers of surveillance, monitoring, arrest, interrogation, referral, and killing under torture or through medical neglect, these branches turned into dark command rooms that generated mass detention orders, drafted charges, and set the pathways of referral into the military and exceptional judicial system, including to military prisons.

In this way, the Division’s central branches became the node at which information arriving from below intersected, allowing individuals and areas to be reclassified and redirected into coercive trajectories that most often ended in basements, the corridors of military courts, then Sednaya, and mass graves. The latter was a destination that could precede any other formal procedure after arrest.(55)

After reviewing the Military Intelligence Division’s central branches in Damascus and their role in planning, coordination, and managing major files at the level of the state, a second tier of the Division’s organizational structure becomes visible: the regional branches spread across the provinces.

B- Regional Branches

The regional branches were the Division’s direct executive arm across Syrian territory. The Division’s regional branches were distributed across 12 branches in several Syrian provinces and held powers of interrogation, arrest, and surveillance at the provincial level. They in turn had detachments in other administrative units, and military security officers and NCOs were present in villages, towns, and institutions, ensuring an intimate security presence woven into the social and political fabric almost everywhere.

In this way, the apparatus’s powers flowed from the central level down to the provincial level through a ramified network of offices, checkpoints, and liaison officers, turning the Division into a multi-layered surveillance system that worked to control both army and society at the same time.

Branch 227, Damascus & its Suburbs

Branch 227 was one of the Military Intelligence Division’s principal regional branches. Known as the Region Branch, it was responsible for Damascus and its suburbs (Rif Dimashq). Branch 227 ran military security operations in Damascus alongside other branches, and its presence in the capital allowed its work to overlap extensively with the Division’s central branches.(56)

The branch gathered information on security, political, and social conditions; monitored opposition activity, both civil and armed; and managed a wide network of local informants; while leading raids and arrest campaigns in coordination with other branches in the Division and with the rest of the security services.

Its role was not confined to field monitoring. It also functioned as a place of detention and interrogation, where security interrogations were conducted and the files of large numbers of prisoners were handled. Branch 227 exercised clear authority over Sednaya Prison, and it was directly implicated in a large number of prominent crimes and violations.(57)

The Region Branch had a general structure that can be generalized to all the regional branches in the provinces. It was headed by a brigadier general, and he was assisted by another brigadier general who served as his deputy. Reporting to the branch leadership were a number of offices and sections, among them: the Information Section, the Interrogation and Prison Section, the Counterterrorism Section, the Military Security Section, the Counter-Espionage Section, and the Administrative Office Section, along with other specialized sections and geographic sections distributed across certain administrative units.(58)

Branch 265, the Sweida Branch

Branch 265 was one of the Military Intelligence Division’s principal regional branches in southern Syria. Headquartered in the city of Sweida, it had a Daraa Section attached to it, and it oversaw military security operations in both Sweida and Daraa provinces. It also had subordinate sections and stations, such as the Ezraa Station and the Sanamayn Section, whose work it coordinated and linked directly to the Division’s headquarters in Damascus as the branch responsible for the south.(59)

In terms of tasks, Branch 265 managed the security file in the two provinces by gathering information on political and social mobilization, issuing wanted bulletins for those sought by the security services, and leading arrest and raid campaigns, as well as organizing the security settlements file with former opponents and local armed factions. Its name became particularly associated with overseeing loyalist armed formations in the south and with controlling networks of local intermediaries in settlement processes or the financial extortion of wanted persons in both Daraa and Sweida. This involved demanding sums of money in exchange for removing their names from security lists or easing the surveillance on them.(60)

In addition, Branch 265 was part of the Military Intelligence Division’s detention network. It was one of the main places of detention to which detainees from the south were transferred or through which other detention facilities were managed. The branch appears in lists of actors implicated in arbitrary detention, torture, and ill-treatment.(61)

Branch 220, the Saasaa Branch

Branch 220 was known as the Front Intelligence Branch, and also as the Saasaa Branch, or as the Quneitra Intelligence Branch. Its headquarters was in Saasaa, in western Rural Damascus, and its area of operations extended across the Quneitra front, the occupied Golan, and western Rural Damascus (Kanaker, Beit Jinn, Mount Hermon and its surroundings). It had detachments and offices in areas such as Khan al-Sheih and its (Palestinian) camp, and at contact points with front-line forces and international forces deployed to monitor the ceasefire lines. According to Syrian and international human rights and research sources, the branch specialized in the intelligence file related to frontline forces deployed along the ceasefire lines and in monitoring military and civilian activity in this particularly sensitive area.(62)

Branch 220 gathered and analyzed information on the movements of army units deployed along the front, monitored local factions and allied militias, tracked residents in border villages and towns in terms of loyalties and cross-border contacts, and led security settlement processes and the management of local intermediaries in the area. Its mode of operation shows that it combined the role of a regional branch—monitoring the local community, running an informant network, and managing raid and arrest campaigns—with that of a frontline branch dealing with forces deployed on the lines of contact and with international forces, while maintaining its own detention and interrogation facility as part of the Military Intelligence Division’s detention system.(63)

Branch 261, the Homs Branch

Branch 261 was the Homs regional branch of the Military Intelligence Division, responsible for the military security file in Homs Province, including oversight of the military units deployed there and the intersections between the military and civilian spheres in the province. Its main headquarters was in the Mahatta neighborhood of Homs city, opposite the train station, and consisted of multiple buildings used as security offices and as detention and interrogation facilities.(64)

Branch 261 managed the military security network in Homs by supervising military security officers and personnel seconded to the area’s military formations and monitoring their movements and degree of loyalty, as well as running a network of sections and detachments at the level of towns and cities according to the Military Intelligence Division’s hierarchical structure (apparatus–branch–section–detachment). The branch gathered intelligence on neighborhoods and villages that witnessed protests or opposition activity, organized raids and arrest campaigns in coordination with other services, then interrogated prisoners and transferred some of them to central branches or to military prisons.(65)

Branch 219, the Hama Branch

Branch 219, the Hama Military Security Branch, was the Military Intelligence Division’s regional branch in Hama Province. It oversaw the entire military security apparatus in the city and its countryside. The branch monitored security and military conditions in the province, gathered information on political and civil activity, and tracked conscripts, soldiers, defectors, and those wanted by the security services, in addition to coordinating with detachments deployed in towns, cities, and military points across Hama’s territory.(66)

Branch 219 played a central role in maintaining the regime’s security grip on Hama, especially after 2011. The branch perpetrated torture and inhuman treatment of civilian and military prisoners before they were transferred to central branches or to military prisons. It is noted that the branch founded and armed loyalist local militias in Hama, including groups known as Suqour al-Assad, making it a key node in the network of official and semi-official violence in the province.

Branch 223, the Latakia Branch

Branch 223 was a regional branch referred to as the Latakia Military Security Branch. Based in Latakia Province, it managed the military security file on the coast and its surroundings, including monitoring the military formations deployed in the area, controlling political and social activity, and running a network of local informants tied directly to the Division’s branches in Damascus. Like other branches, it served as a detention and interrogation facility, and cases of torture, ill-treatment, and inhuman detention conditions were documented there.(67)

Alongside its role as a regional branch, Branch 223 was the organizational front for a network of loyalist militias—foremost among them the Military Security Shield Forces, established in early 2016 as a semi-autonomous paramilitary unit directly subordinate to the branch in Latakia in an effort to reinforce its influence and compensate for the regime’s manpower shortages. These forces took part in fighting along the coast, in Homs, and in Tadmor. The branch also played a key role in arming and organizing popular committees along the coast.(68)

Branch 256, the Tartous Branch

Branch 256 was the Military Intelligence Division’s regional branch in Tartous Province, responsible for managing the military security file in the city and its coastal countryside. It had field detachments and sections at the level of administrative units across the province. Following the pattern used at other provincial branches, Branch 256 gathered information on political and social activity in Tartous and its countryside, monitored the loyalties of the military formations deployed in the area, and ran a network of informants in official institutions and civilian sectors.(69)

It also issued security bulletins and arrest warrants for wanted persons and coordinated with other Division branches and security services in raids, arrest campaigns, and the transfer of detainees. Branch 256 functioned as a main detention and interrogation center along the Syrian coast, receiving civilian and military prisoners from the area before some were referred on to central branches, making it a key link in the chain of arrest and repression on the coast.(70)

Branch 271, the Idlib Branch

This branch managed the military security file in Idlib Province and had detachments at the level of districts and sub-districts. It monitored the situation of military units deployed in the area, watched political, social, and civil activity, and ran a network of local informants in cities, towns, and villages. Branch 271 was directly implicated in suppressing demonstrators in Idlib and in committing violations and crimes against humanity.(71)

In terms of structure and function, Branch 271 operated as a self-contained node that combined intelligence gathering, command of field operations, and management of arrest and interrogation. The branch included a detention facility used to hold and interrogate detainees before transferring them to central branches. The fall of the branch from the Assad regime’s grip during the liberation of Idlib city in 2015 helped shed light on how these branches operated. The regime later reopened the branch in the nearby town of Khan Sheikhoun when it regained control over that area.(72)

Branch 290, the Aleppo Branch

Branch 290 was responsible for the military security file in the city of Aleppo and its countryside, including monitoring the military units deployed in the area and managing the overlap between the military and civilian spheres in the province. In addition to its main headquarters, the branch ran a large number of detachments in the city and its wide rural hinterland and participated in managing checkpoints jointly with other security services.(73)

For many years, the branch was part of the structure responsible for repression and violations, and it also served as a main military security detention facility. Dozens of cases were documented of prisoners being killed, tortured, or subjected to inhuman treatment there. With its dual function as regional security command and detention and interrogation center, Branch 290 was one of the Military Intelligence Division’s most important tools for controlling Aleppo and managing its arrest and repression system.(74)

Branch 243, the Deir ez-Zor Branch

Branch 243 was the Deir ez-Zor provincial branch. It oversaw security in both Deir ez-Zor and Raqqa Provinces, and had sections and detachments under its authority in the cities and towns of those provinces. The most important was a section in Raqqa city, since there was no separate military security branch in Raqqa Province. The branch gathered information on political, military, and opposition activity and ran a wide network of informants.(75)

Alongside its security tasks in the civil sphere, the branch monitored military units and the loyalty of soldiers within them, as well as the Iraqi border. Branch 243’s headquarters served as a detention and interrogation center, like other security branches under the Military Intelligence Division, before prisoners were sent on to central branches as needed.(76)

Branch 222, the Hasaka Branch

Branch 222, known as the Hasaka Military Security Branch, managed the security and military file in the entire province. Its main headquarters was in Qamishli, with a section in the security compound of Hasaka city. The branch building was used as a detention and interrogation facility under the Military Intelligence Division; cases of torture, ill-treatment, and inhuman conditions of detention were documented there.(77) The branch’s mandate included monitoring the military units deployed in Hasaka and tracking political, security, and civil activity. It operated in a highly complex environment where the jurisdictions of the Assad regime, the Syrian Democratic Forces, and other local actors overlapped.

In terms of detailed tasks and structure, Branch 222 functioned as a link between the Division’s leadership and central branches and the local network of sections and detachments deployed in the province’s towns and cities. It supervised the running of informants, collected daily reports on opposition activity and social mobilization, and managed security coordination with the forces holding ground locally.

Branch 221, the Badiya (Desert) Branch

Branch 221, also known as the Badiya (Desert) Branch, or the Tadmor Branch, was headquartered in the city of Tadmor in eastern Rural Homs in the Syrian desert. The branch was tasked with security in the Badiya and the area around Tadmor; it covered desert supply routes and the axes linking central and eastern Syria, and ran a network of detachments and posts along main roads and in some desert towns.(78)

Branch 221’s tasks revolved around security and military surveillance of the Badiya and the Tadmor area: gathering information on the movements of military units and allied and opposition militias, controlling desert roads and supply lines, and participating in security operations against civilians and local communities in the area.

The branch served as a detention and interrogation center in the military security detention network. It was also cited as having coordinated with army formations around the 55-kilometer zone east of Homs in implementing a policy of siege and starvation against the Rukban camp and desert residents, and in carrying out arrest campaigns targeting civilians in Tadmor and its surroundings.

An examination of the Military Intelligence Division’s regional branches shows that they were not merely local arms executing orders from the central headquarters, but integrated nodes with a relatively autonomous ability to observe, assess, and take initial decisions on arrest, interrogation, and referral. Through their spread across the provinces and their networks of informants, sections, detachments, and checkpoints, these branches became the Division’s daily face in society. They decided who was “wanted” by the security services, effectively managing the initial stages of detention, and controlling the fates of individuals and local communities across wide geographic spaces.

These branches also formed the operational base for a system of repression that reproduced the center in the peripheries and linked field-level surveillance in neighborhoods and villages to the system of prisons and military and exceptional courts in Damascus and elsewhere. For most prisoners, their journey began in these branches with a summons, a raid, or a checkpoint stop, followed by interrogation and initial detention, and ending in referral to central branches and then to military prisons.

Through their direct contact with society, the regional branches played a decisive role in entrenching the logic of the “security state”. The proliferation of branches and the scale of crimes they left behind over decades complicates any future path towards transitional justice and security-sector reform.

Figure (4): Structure of the Military Intelligence Division

III. Instruments of Repression Used Against Society

The Assad regime relied on a broad arsenal of repressive tools to tighten its security grip throughout its years in power, and especially during the years of the revolution; in that period practices that had once been applied to select cases were deployed on a wide and systematic scale.(79)

These tools ranged from comprehensive surveillance of every part of society, through campaigns of arbitrary detention based on lists of wanted persons, to preventive arrests aimed at blocking any protest before it began, and finally to random arrests and detention in harsh conditions that, in many cases, led to prisoners being killed under torture, dying as a result of medical neglect, or being executed through military courts.

The same repressive system also involved the systematic use of torture and the erasure of its traces from official records; the exploitation of informants to sow division and suspicion within society; and the repeated transfer of prisoners between security branches to obscure the abuses committed against them.

Comprehensive Surveillance

Security documents show that the Syrian intelligence services adopted an all-encompassing approach to monitoring society; no aspect of daily life remained beyond the gaze of the Military Intelligence Division. Many of the records contain entries concerning surveillance and observation operations, revealing how deeply security oversight penetrated into the most ordinary details of daily life.

These security operations included wiretapping telephone calls and tracking people’s movements and activities, even when the surveilled citizens posed no direct security threat. Surveillance did not stop at ordinary citizens; it extended to army personnel and state officials themselves. Several pages show security branches spying on officials in other agencies and exchanging recordings of their internal calls. This mutual eavesdropping among the security services reflected a profound level of suspicion and distrust inside the apparatus of power itself.(80)

The strategy of comprehensive surveillance relied on several tools, foremost among them telephone interception and a network of informants spread across society. The documents contain no indication of court orders or legal procedures authorizing this enormous volume of wiretapping and other forms of spying, suggesting that the security services acted entirely beyond judicial oversight and in the absence of the rule of law.

The Military Intelligence Division played a central, often dominant role in surveillance and spying. This is consistent with the prevailing perception of its control over the Syrian security landscape. Security monitoring in Syria was marked by its breadth and deep reach into both private and public spheres. It formed a core pillar of the system of repression that was designed to detect any sign of dissent and smother it at inception.

Arbitrary Detention & Wanted Lists

The Military Intelligence Division’s records document a systematic pattern of arbitrary detention underpinned by expansive wanted lists. In the sample examined, 576 pages, representing roughly 11 percent of all pages, contain references to prisoners or people sought for arrest. This figure reflects the mass arrest campaign that the Assad regime used to suppress opposition, beginning in 2011.(81) The documents show that these detentions reached a wide range of groups; they did not stop at political activists, demonstrators, and critical journalists labeled in security reports as “hostile media”, but also encompassed defected soldiers and those suspected of belonging to opposition militias.

Wanted lists circulated at military checkpoints played a central role in facilitating the campaign of arbitrary detentions. The post-Assad Interior Ministry later revealed that millions of people had been listed as wanted by the Assad regime and removed their names from travel-ban rolls(82) The Ministry also stated that the Military Intelligence Division had issued the largest number of arrest warrants.(83) As a rule, these wanted lists contained direct orders to detain named individuals, and at times requests from security branches for additional information about people already marked as wanted.

The documents also reveal clear patterns in how arrests were carried out. Most cases recorded concerned people detained for expressing opposition by participating in protests or by merely uttering a critical remark in a private gathering. In its repressive practice, the Assad regime did not distinguish between the civil and armed opposition; non-violent demonstrators and critical journalists were frequently placed with members of alleged rebel or terrorist groups under the catch-all label of “inciting elements”. This vague charge served to justify detaining everyone without distinction. The records likewise show how readily the security services violated the law: they continued to carry out arrests without proper judicial procedures even after the Assad regime announced the lifting of the state of emergency in April 2011. That measure can be seen as purely cosmetic, leaving the security grip intact.(84)

The motives and mechanisms of arrest clearly point to the absence of any genuine legal frame and to the reliance on denunciations, suspicions, or confessions extracted under torture. People were often arrested on the strength of reports filed by informants, acquaintances or even family members, who claimed that the person intended to take part in, or had taken part in, activities opposed to the regime. Others were detained because their names appeared in an order sent from a security branch or on a wanted list, perhaps after they had been seen on an opposition media outlet or flagged through surveillance as allegedly preparing anti-regime actions. In some branches, the net was flung further still; the relatives of wanted individuals were held as hostages to pressure the primary target to turn himself in. This was a form of collective punishment that ran counter to every principle of justice. Security personnel also carried out on-the-spot arrests if they had personally witnessed behavior deemed hostile to the regime.

What underlined the arbitrariness of these measures was that the security services rarely verified the credibility of information before carrying out an arrest; no serious inquiry was conducted to test the allegations until after the suspect had been thrown into prison. Even if it later became clear that the suspicion was unfounded or the report malicious, this did not lead to the prisoner’s immediate release. Instead, the security services conducted retroactive searches for any other information that might link the prisoner to oppositional activity, in order to justify keeping him or her in custody. This logic of “arrest first, investigate later” cemented the punitive and arbitrary nature of the security services’ work.(85)

Preventive Arrests to Block Protest

The security services used preventive arrest as a tool to suffocate protest at its inception. Rather than waiting for demonstrations to break out and then crushing them by force, the regime moved to detain potential activists in advance, in order to prevent protests from taking shape at all. One daily security report recorded an anticipated drop in the number of demonstrators at a planned protest precisely because the authorities had already arrested many of those expected to participate.

Other documents contain explicit references to holding people in order to dissuade them from taking part in future demonstrations, by instilling fear about the consequences of protest. Arrest policy did not focus only on punishing those who expressed opposition; it became a preemptive measure that, in practice, undermined the right to peaceful assembly before it could be exercised. This proactive security strategy underscored the regime’s determination to strip the popular movement of its core organizers and paralyze its capacity to mobilize through precautionary arrests, in clear violation of internationally protected rights to expression and assembly.(86)

Detention in Conditions that Lead to Loss of Life

Documents, survivor testimonies, and human rights documentation point to a recurring pattern of prisoners dying in Syrian detention centers in circumstances that suggest the conditions of detention themselves—torture, ill-treatment, and denial of medical care—were a direct factor in loss of life. The deaths were often recorded in official registers using formulations such as “sudden cardiac arrest,” or attributed solely to injuries that the person had sustained at the moment of arrest or in battle. External evidence, however, from the bruises, wounds, and long surgical sutures visible on the bodies, points to levels of violence that cannot be reconciled with the official accounts. This discrepancy between security narratives and medical-physical evidence raises serious doubts about the credibility of the stated causes of death and suggests that medical-security narratives were being used as tools to conceal what prisoners endured while in custody.(87)

These were not isolated cases; they formed part of a broader pattern of violations of prisoners’ right to life in closed detention environments that lacked even minimal transparency or oversight. Government records rarely acknowledged deaths under torture or due to denial of treatment, while international and Syrian human rights organizations documented large numbers of deaths in prisons and security branches attributed to systematic torture, malnutrition, overcrowding, and the absence of adequate medical care. In this structural absence of transparency, tracing responsibility for these deaths has become a complex task, yet the accumulation of testimonies, photographs, and leaked documents provided strong indications that many deaths in detention were not accidental events but the direct outcome of policies and practices that turned the detention environment itself into one conducive to loss of life.(88)

Torture & its Concealment

A close reading of security documents reveals a consistent pattern of deliberate silence around torture. Official correspondence was almost entirely devoid of any direct acknowledgment that it was being used, despite the abundance of former prisoners’ testimonies and human rights reports confirming its prevalence and systematic practice in Syrian detention centers. This absence was no accident; it pointed to a deliberate policy of keeping torture off the written record, whether to avoid leaving evidence that could later be used in legal proceedings, or to preserve a formal façade of “orderly” operations that presented the services as working within a regulated legal and procedural framework.(89)

Even so, the documents were not entirely free of indirect signs that torture sat in the background. Some pages, for instance, contained statements written in prisoners’ own hand, asserting in formulaic language that they had not been beaten or mistreated. These formulations read less like genuine accounts of treatment than dictated texts designed to preemptively deny charges. Security memoranda also repeated vague phrases such as “take the necessary measures” or “address the situation of the person mentioned,” without specifying what those measures entailed. Such wording left ample room to read them as linguistic cover for unlawful practices that might include torture or liquidation, while preserving a wide margin for denial. In this sense, silence and euphemism in the agencies’ records became part of the architecture of the crime itself: torture was a central, ever-present practice in the work of the apparatus, yet it was deliberately excluded from the page, a choice that provided additional protection for perpetrators inside the closed circuits of repression.(90)

Using Informants to Ignite Feuds in Society

The security documents revealed an organized pattern in the use of informants as one of the pillars for managing and controlling social conflict. With the outbreak of the revolution, the Military Intelligence Division activated its informant networks on a broad scale, planting them as embedded agents in protest gatherings to monitor and fragment them from within, and turning everyday life into a space from which opinions and positions could be reported. A review of the files showed that a substantial portion amounted to lists of informants’ names and their reports; the content of those reports ranged from denouncing individuals for expressing critical views of the regime to accusing others of purported ties to “armed elements” or “terrorists”.

The security services often treated these reports as sufficient grounds for immediate arrest, within a policy built on “arrest first, verify later.” In practice, this meant that malicious or unsubstantiated information produced real harm for innocent people long before its accuracy was ever tested. (91)