Co-Authors:

The Referral of Civilians to Military Prisons During the Syrian Revolution: Procedures, Pathways, and Judicial Gateways (Sednaya Prison as a Case Study)

Summary

- This study explores the phenomenon of referring civilian detainees to military and exceptional courts during the Syrian Revolution (2011–2024), a process that often led to their transfer into the military prison system—most notably, to Sednaya Prison. The study examines the dimensions and consequences of this phenomenon, which became one of the most expansive and complex tools of institutional violence in Syria. What had initially been a legal exception—the referral of civilians to military courts—evolved into a systematic path involving the security apparatus, the judiciary, and even certain state institutions. This created an integrated system of enforced disappearance, torture, and execution.

- To address the research questions and challenges, the study draws on both primary and secondary sources. These include thousands of documents from the security agencies discovered after the fall of the regime, in addition to field interviews with former prisoners, judges, lawyers, defected officers, and officials from human rights organizations. The research also reviews relevant legal texts and both local and international reports.

- The first chapter outlines the main security agencies and administrative structures that operated in Syria prior to the fall of the Assad regime, analyzing their formal mandates versus their actual practices. By mapping out and deconstructing the security apparatus—which acted as the primary authority over arrests—the study provides essential context for understanding the detention system that operated over decades, and particularly its operations during the revolution. It also helps explain how civilians were funneled into military detention centers, above all Sednaya Prison.

- The second chapter traces the path of civilian detainees after their detention by the security branches, focusing on the process of assembling their referral files from security agency detention centers to the “authorities” (judicial or otherwise) that would ultimately decide their fate. This section seeks to map the possible referral pathways from within the security agencies, with a particular focus on those leading to Sednaya. It also analyzes the criteria that determined which detainees were sent where.

- The third chapter follows the referral of civilian detainees into the military and exceptional judicial system, shedding light on the powers, procedures, and rulings of these courts as judicial gateways to Sednaya. This is crucial for understanding how legal and security institutions were integrated to produce a system that funneled civilians into Sednaya, whether as a site of long-term disappearance or as an execution ground.

- The significance of this study goes beyond analyzing and documenting a phenomenon that may seem concluded with the fall of Assad and the closure of the prison. It aims to prevent the re-emergence of similar systems by supporting efforts toward accountability and transitional justice, reinforcing mechanisms for locating the missing, and contributing to the broader discussion about judicial and security reform in Syria. Accordingly, the study offers a series of recommendations at various levels.

The liberation of Sednaya Military Prison marks more than just the end of a notorious facility. It represents the collapse of a peak in the repressive system and a rare opportunity to rebuild justice from the ground up. It is a moment to redefine the relationship between the state and its citizens based on rights, not fear, and grounded in memory, not denial. Despite the challenges, this path is the precondition for any real stability, lasting reconciliation, and a just future for Syria.

Closing the Sednaya file is not only a test of Syria’s collective memory—it is a critical test for the new authorities: will they be as just as the former regime was unjust? And can they build a future in which exceptionalism is not reproduced under a new name?

Introduction

The detention system established and run by the Syrian security apparatus over several decades became one of the most defining features and manifestations of the “savage state” under the rule of the Assad family. This system granted unchecked powers that transcended the law and led to violations of the rights and dignity of individuals, groups, and institutions. It was used to subjugate both state and society, suppress political opponents, and it served as a key tool in consolidating power — eventually becoming one of the main reasons motivating the uprising against the regime.

Within this system, detention centers played a central role in sustaining a structure of fear and repression. Just as Tadmor Military Prison came to symbolize terror in the public consciousness during Hafez al-Assad’s rule, Sednaya Military Prison became the most brutal location under Bashar al-Assad, especially following the start of the Syrian revolution in 2011.

Despite their military nature, these facilities became the final destination for tens of thousands of civilians, who reached them through various pathways and procedures. From the onset of the Syrian revolution in March 2011, arbitrary arrests targeting civilians increased dramatically. Instead of being referred to civil courts, thousands were sent to military and/or exceptional courts — judicial bodies created by special decrees and operating outside the regular legal framework under exceptional laws and procedures(1) — in complete disregard for the basic standards pertaining to fair trials. These referrals led tens of thousands to military prisons, most notably Sednaya, which transformed into a symbol of systematic and bloody repression.

The complex pathways leading civilians to military prisons, especially Sednaya, cannot be understood without first analyzing the structure of the institutions and agencies that enabled them — at the core of which were the security agencies. Sednaya was not merely a detention facility; it was the endpoint of a tightly interlinked administrative-security-judicial process. This process typically began with an arrest by one of the security branches or their affiliated militias — a first step on the road to Sednaya.

In turn, any attempt to understand and deconstruct the formal pathways through which civilians were referred to military prisons cannot be complete without confronting the broader judicial system in Syria under the rule of the Assad family — especially its military and exceptional branches. These branches are among the clearest manifestations of how the security apparatus came to dominate state institutions. Over time, they were transformed into obedient tools in the hands of the security agencies, used to suppress political opponents and refer tens of thousands of them to military prisons. This system thrived on a wide-ranging and vague legal framework that enabled the expansion of exceptional trials beyond constitutional limits. Referrals to military or exceptional courts were not random. They followed complex and undeclared criteria that combined political-security considerations with personal, sectarian, and economic factors. The result was a violent referral system, entirely removed from civilian oversight, that ultimately led to gross violations and crimes against humanity — as documented by multiple local and international organizations.(2)

The phenomenon of referring civilians to the military or exceptional judiciary—and, by extension, to military prisons—is not new in Syria. It took root in the 1960s as the political role of the armed forces grew, especially after the Baath Party coup which seized power in March 1963. In the years that followed, the regime set up Military Field Courts and the State Security Court, both of which ignored normal judicial limits and expanded the prosecution of civilians. The pattern intensified once Hafez al-Assad formally took power in March 1971, when these courts became a tool for legitimizing violence against opponents, particularly political ones.(3) The same approach persisted throughout the era of his son Bashar al-Assad (July 2000 – December 2024).

After the Syrian revolution began, and despite the abolition of the State Security Court in 2011, the system of exceptional justice remained intact. In 2012 the regime created the Terrorism Court, which replicated those extraordinary practices and, alongside the Military Field Courts, helped eliminate revolutionary prisoners—civilian and military alike. Tens of thousands were funneled to Sednaya Prison as the final stop. Sednaya was a site of detention and enforced disappearance where the most brutal violations were committed, including torture in all its forms as well as outright executions.(4) These abuses continued systematically until the fall of the Assad regime on December 8, 2024.

Against this backdrop, this study examines the referral of civilian prisoners to military and exceptional courts during the 2011–2024 Syrian Revolution—a pathway that most often ended in the military prison system, above all in Sednaya. The inquiry begins by mapping and deconstructing the various security agencies and directorates—their structures, administrative subordination, jurisdictions, and powers—because they form the base and starting point of that pathway.

The study continues to track the path of detainees after they were detained in security branches. Its aim is to clarify the procedures related to the formation of the referral file and the possible paths it took after the security agencies, with a focus on those that led to Sednaya Military Prison. It then moves on to discuss and analyze the criteria—both procedural and legal—that determined this particular destination over others. This is done through an in-depth examination of the military and exceptional judiciary systems, which serve as a “legal” cover and a near-certain gateway into Sednaya Prison. It also explores the nature of their jurisdictions, rulings, and the procedures governing trials within them.

The importance of this study stems from the gravity of the issue it addresses: the phenomenon of referring civilians to military and exceptional courts during the Syrian Revolution, and the consequences that followed. It focuses in particular on Sednaya Prison as a stark example of the deadly outcomes of these referrals, which led to the deaths of tens of thousands of civilians and became one of the most prominent human rights tragedies of the Syrian Revolution.

The significance of this study lies not only in documenting, analyzing, and discussing a phenomenon that may appear to have ended with the fall of the Assad regime on December 8, 2024, and the release of the remaining prisoners from Sednaya and the closure of the prison, but also in its contribution to preventing the reproduction of this model and the paths that led to it. This is achieved by supporting efforts toward accountability and transitional justice, advancing mechanisms for locating the missing, and enriching debates around reforming the judicial and security sectors in post-Assad Syria.

Accordingly, the study’s central research question is: Why were civilian prisoners during the Syrian Revolution referred to military or exceptional courts instead of civilian ones? What were the criteria governing the referrals to Sednaya Military Prison specifically, and what were the consequences that resulted from these referrals?

Within the scope of this complex question, a series of sub-questions emerge. The answers to these sub-questions form the structure and analytical framework of this study:

- What were the security agencies and administrative bodies responsible for arresting civilians before transferring them to Sednaya Military Prison? What were their administrative affiliations, jurisdictions, and limits of authority?

- What procedures and mechanisms were used to compile the referral file within these security agencies, and what possible pathways might that file follow afterward?

- What were the specific referral pathways that led to Sednaya Military Prison in particular, and what legal or procedural criteria determined that destination over others?

- What judicial gateways led to Sednaya Military Prison? What were the jurisdictions of these courts, the nature of their rulings, and the legal processes that took place within them?

To answer these questions, the study adopts a descriptive-analytical methodology combining observation and documentation of the phenomenon as it was practiced in reality, and supporting the analysis of its complex dimensions (legal, security, political) through both qualitative and quantitative tools. It relies on two main types of data sources, primary and secondary, used complementarily to understand and analyze the phenomenon under study. These are distributed as follows:

- Security apparatus documents: The research team reviewed more than 300 documents from Sednaya Military Prison obtained after the fall of the Assad regime. It also analyzed files issued by the Air Force Intelligence Directorate and the Military Intelligence Division, which includes data on more than 100, 000 prisoners and their referrals (under interrogation – referred) from the beginning of the revolution through 2017. In addition, the team reviewed over 100 documents directly related to the operations of the Military Police.

- Field interviews: To deepen understanding of certain details and verify specific information, the research team conducted no fewer than 30 field interviews with various individuals connected to the subject of the study. These included: former prisoners in Sednaya Military Prison, defected military judges, lawyers, former officers from the security apparatus, and human rights activists.

- Relevant studies, papers, and human rights reports: The study also relies on reports issued by local and international organizations, particularly those that address the issue of prisoners during the Syrian Revolution. These focus on those brought before military courts or survivors of military prisons.

- Legal and constitutional texts: The research team reviewed legal and constitutional materials related to the authority and jurisdiction of the security apparatus and military and exceptional courts in Syria. These texts and regulations were analyzed using a comparative method that contrasts the legal text with actual practice. The analysis also differentiates between formal judicial referrals and the real security procedures that determined the fate of the prisoners — especially in cases involving referral to Sednaya Military Prison.

I. The Beginning of the Process: Security Agencies in Syria (Structures and Authorities)

This chapter focuses on mapping the main security agencies and departments in Syria before the fall of the Assad regime. It outlines their core structures, administrative hierarchies, and theoretical jurisdictions compared to the powers they actually wielded in practice. Analyzing Syria’s security apparatus— the primary authority responsible for arrests—can greatly aid in understanding the detention system that these agencies operated for decades, and especially after the revolution began in 2011. It also helps clarify the pathways through which civilian detainees were transferred from these agencies to detention centers, most notably Sednaya Military Prison.

Main Agencies: The First Gateway to Sednaya Prison

The Syrian security apparatus was built as a multi-headed hierarchy. But the decision-making power remained firmly centralized in the hands of the President of the Republic, who was also the Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Armed Forces. Power within this apparatus was primarily distributed among four main intelligence agencies(5):

Military Intelligence Division

The Division of Military Intelligence is one of the oldest intelligence services in Syria. It was officially established in its current form in 1969, though it had previously been known as the “Second Bureau,” whose origins date back to the French Mandate period.(6) Later, the division—also known as “Military Security”—became one of the key intelligence branches under the Assad regime.

Although it was formally affiliated with the General Staff and thus the Ministry of Defense, the Division of Military Intelligence played a decisive role in appointing both the Chief of Staff and the Minister of Defense. It was also connected to the National Security Office.

The division’s responsibilities included gathering military intelligence, securing borders, monitoring military communications, and overseeing the conduct of military personnel to detect internal security threats. It was also responsible for monitoring military detention centers.

Its role was not limited to military affairs. It was extensively involved in arrest operations, detentions, and enforced disappearances. Among all the security branches, it issued the highest number of arrest warrants for Syrian civilians.(7) Additionally, it wielded significant influence within the military itself.(8)

The Division adopted a three-digit numerical reference system to code its branches, both the central ones in Damascus and the regional branches in the governorates. Its main central branches included: the Interrogation Branch 248, the Palestine Branch 235, the Raid Branch 215, the Regional Branch in Damascus 227, and Branch 290 in Aleppo. In addition, the Division maintained subsidiary sections in various cities,(9) along with hundreds of checkpoints and detachments manned by its personnel—especially after 2011.(10) Over subsequent years, the Division also founded a large number of affiliated militias that performed the same roles assigned to its personnel, particularly in carrying out arrests and abuses; the most prominent of these militias was the “Military Security Shield”.

Air Force Intelligence Directorate

The Directorate of Air Force Intelligence is one of the most prominent and powerful Syrian intelligence agencies. It crystallised as an institution in 1970 under Hafez al-Assad, who relied on it heavily because of his background as a former commander of the Air Force. Despite its formal subordination to the Air Force and Air Defence Command, and therefore to the Ministry of Defense,(11) it in fact operated as an independent body, bypassing the traditional military chain of command. The Directorate gathered information concerning the security of the President of the Republic and the Presidential Palace, monitored airports and air traffic—especially military traffic—kept watch over, and guaranteed the loyalty of, personnel in the army and the other security agencies, including wire-tapping and surveillance of security and military officials. It also carried out special military operations and at times assumed full combat roles.(12)

Unlike the other intelligence agencies, Air Force Intelligence did not employ a three-digit numbering system for its branches. Instead, it named its regional branches after the country’s five military zones.(13) The Directorate also maintained sections, detachments, and checkpoints in numerous cities, and in Damascus it had central branches headed by “the Interrogation Branch” and “the Special Missions Branch”, among others.(14)

Together with the militias it established for its own benefit, especially after 2011, the Air Force Intelligence Directorate played a central role in implementing wide-scale arrest campaigns against civilians. It carried out arbitrary arrests of political activists and participants in demonstrations, as well as civilians merely suspected of opposing the regime.

General Intelligence Directorate

Known formerly as “the Directorate of State Security” before its name was officially changed to the Directorate of General Intelligence,(15) this functioned as an independent body reporting directly to the Presidency and was not subject to any ministerial authority. The Directorate was tasked with multiple missions in both domestic and external intelligence gathering, including counter-espionage, monitoring journalists, political activists, opposition figures, and suspects in so-called “terrorism” cases, in addition to clerics.(16)

The Directorate adopted a three-digit numerical reference system to code its branches, similar to the Military Intelligence Division. It comprised several central branches in Damascus, most notably the Interrogation Branch (285), the External Branch (279), and the Counter-Espionage Branch (300). It also maintained branches in nearly every Syrian governorate; the best-known were the Internal Branch (251), also called the Khatib Branch, in Damascus, along with Branch 322 in Aleppo, Branch 320 in Hama, and Branch 318 in Homs. The Directorate likewise operated sections, detachments, and checkpoints spread across the country.(17)

Like other intelligence agencies, the General Intelligence Directorate played a central role in implementing the Assad regime’s systematic repression policies. It was responsible for a large number of arrests and served as a main actor in the network of abuses designed to terrorize society and extinguish any signs of opposition.

Political Security Division

The Political Security Division was the smallest of the security agencies in size. Administratively it fell under the Ministry of the Interior, yet the Minister of the Interior had no real authority over its work beyond administrative and logistical matters. In fact, the Division actually monitored the Ministry of the Interior itself—from the minister down to the lowest-ranking member—meaning the ministry did not oversee its intelligence activity. The head of the Division was therefore more powerful than the Minister of the Interior, especially because he enjoyed a direct relationship with the President of the Republic.(18)

The duties of the Political Security expanded to include monitoring civil society, political life, cultural and student activities, political parties, religious activities, and Arab affairs, in addition to supervising the police. The Division maintained several central branches that handled political, economic, and other key fields, most notably: the Interrogation Branch, the Arab and Foreign Affairs Branch, the Parties and Associations Branch, the Economic Security Branch, and the Police Security Branch. It also operated regional branches in every Syrian governorate except Quneitra, along with sections and detachments in many cities.(19)

The Division was one of the security agencies most deeply embedded in society and in direct contact with civilians, covering the entire country and all social strata. Many citizen transactions and applications for business or facility licenses required approval from the Political Security Division, which functioned as the regime’s reservoir of information on its citizens.(20)

Alongside the other intelligence services, the Division pursued systematic policies that included arbitrary detention in its own detention centers. It became a tool for suppressing any oppositional activity, relying on enforced disappearance and inhuman treatment of detainees.

National Security Office

The National Security Office formed the main connecting point for the four security agencies listed above. It supervised, coordinated, and guided their work. By virtue of its direct insight into the agencies’ activities, the Office served as Bashar al-Assad’s chief advisory body on matters of national security, negotiations, and other internal and external security affairs. Nevertheless, the Office wielded no real authority over the agencies; decisive power remained with the head of the regime and the officers who led those agencies.(21)

The Office consisted of a director and the heads of the four principal security agencies, who sat as permanent members. It did not include representatives of the Military Police or the civil police. Decisions adopted by the Office were transmitted to the competent civilian, military, and security bodies for execution. After 2011, the Office became the primary bureaucratic destination for security referrals originating from the intelligence services. It reviewed every referral and granted approval for implementation, especially those that routed prisoners to Sednaya Military Prison.

Auxiliary and Supporting Agencies

Military Police

The Military Police formed an essential organisational pillar of the detention and enforced-disappearance system. The corps was led by a Major General and operated under the Chief of the General Staff, within a hierarchy that ultimately reported to the Minister of Defence. Its remit expanded long ago beyond enforcing discipline inside the armed forces to supervising the transfer of civilian and military detainees, maintaining their records—including death registers inside places of detention—and protecting those facilities as well.(22)

Perhaps the strongest reason for discussing the Military Police within the main structures of the security agencies that ran the detention system is that, in addition to its other duties, it held direct responsibility for administering Syria’s military prisons. These prisons fell under the immediate supervision of the Military Police – Interrogation and Prisons Branch, with no civilian or independent judicial oversight whatsoever.

Documented testimonies confirm that torture, ill-treatment, and enforced disappearance were not exceptions in these prisons but a systematic policy in which thousands of Syrians were killed, executed, or disappeared, amid a total absence of even the most basic standards of care and justice—especially in the three best-known facilities during the years of the Syrian Revolution, namely: (23)

-

-

-

- Sednaya Military Prison: This facility was formally called the First Military Prison, and was regarded as the most infamous and terrifying of Assad regime prisons. It lies thirty kilometers north of Damascus, near the town of Sednaya. The prison contains two main buildings. The first features a unique, three-spoked radial design and is referred to as the “Red Building”. It was reserved for prisoners of conscience and for civilians and soldiers held on political grounds. The second main structure, known as the “White Building”, housed army personnel convicted of military offenses connected to the army itself.

- Tadmor Military Prison: It stands in the city of Tadmor (Palmyra) in Homs Province and was notorious for its bloody record long before the revolution, becoming fixed in the Syrian collective memory. In May 2015 ISIS destroyed part of it after seizing the area. Although Assad’s forces later recaptured the site, it remained out of service.

- Baloni Military Prison: Also known as the “Quadripartite Committee” Prison, it was formally called the Third Military Prison and is located in the city of Homs. It was originally reserved solely for military personnel, but with the onset of the Syrian Revolution it was converted into a facility that held civilians and soldiers alike.

-

-

Military Medical Services Directorate

Military hospitals and health centers fell under the Military Medical Services Directorate, which in turn reported to the Logistics and Supply Authority at the General Staff of the Army and Armed Forces. Although these facilities appeared to be medical units of the army,(24) they performed functions far removed from treatment and care, and instead became administrative tools within the system of abuse. The Directorate, through its military hospitals, played a central role in the detention apparatus—especially after 2011—whether a prisoner was transferred there for treatment or delivered as a corpse ahead of burial in mass graves.

Military hospitals—particularly those in Damascus and its outskirts—played a central role in the machinery of killing prisoners and then concealing the truth. The most prominent facilities were: Tishreen Military Hospital in Damascus’s Barzeh district; the “Martyr Youssef al-Azma” facility, known as al-Mazzeh Military Hospital and coded 601; the “Martyr Doctor Muhammad Obeisi” facility, known as Harasta Military Hospital and coded 600; and the “Martyr Doctor Khaled Saqqa Amini” facility, known as Qatana Military Hospital and coded 605. These hospitals received the corpses of prisoners who had been killed under torture in detention centers, then they officially recorded the deaths as the result of “natural causes,” often without any inquiry or review. On some occasions their own staff perpetrated killings and direct torture against prisoners.(25)

Military hospitals were guarded by the Military Police; each hospital had a dedicated detachment that both secured the prison ward and participated in the abuses committed there. In addition, the Military Intelligence Division stationed further detachments inside some hospitals to reinforce security, monitor their staff, and prevent any news from leaking out.(26)

The names of these hospitals—and others—appear in the testimonies of survivors and defectors as sites where prisoners died, suffered deliberate medical neglect, underwent physical and psychological torture, and were summarily executed in acts rising to the level of genocide. These hospitals also played a central role in forging death certificates and concealing the real causes of killing, making them an active link in the chain of disappearance and deception.

The various security agencies listed above—with their main divisions, the branches and militias they controlled in the governorates, and the directorates linked to them—carried out large-scale arrests, especially after the Syrian Revolution began in 2011. Operating without judicial, administrative, or financial oversight, they wielded absolute powers of arrest, interrogation, and liquidation, while each agency maintained its own prison network and separate operating rules. This security model produced what the UN Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights described as a “multi-headed security state,”(27) where no unified legal standards exist and political, sectarian, and personal considerations dictate life-and-death decisions against civilians: first arrest, then referral to the military or exceptional courts, and finally to a military prison such as Sednaya.

The detainee’s journey began the moment he was seized by one of these branches or other agencies—whether at a military checkpoint, during a home raid, or after being stopped at his workplace or university. No “judicial report” or judicial supervision governed these operations; personnel from the various security agencies, or from army and National Defense units armed with wanted lists circulated by the branches, carried out most arrests without warrants, court orders, or even an explanation of the reason for detention.

II. After Arrest: The Referral File (Procedures, Pathways, Criteria)

From the moment a detainee entered a detention centre run by the security agencies, a chain of procedures began that would determine his subsequent path and fate. That path was traced inside a coercive system that ran parallel to the law while hiding beneath its cover, relying on permanent security opacity and managing detention as a tool of rule, not as a legal procedure. In this system, the security agencies mutated into parallel authorities that overrode and steered the judiciary, producing an “institutional” pathway that channeled civilians toward the military judiciary or exceptional courts—and, by extension, into military prisons, chief among them Sednaya Prison—for the purposes of long-term enforced disappearance or liquidation.

This section follows the journey of civilian detainees after they were taken by the security agencies and their branches, with the aim of clarifying the procedures used to assemble their referral files in security detention centres before those files were sent to the “competent bodies” that would decide their ultimate fate. It identifies the potential pathways through which civilian detainees were referred, highlights those that led to Sednaya Military Prison, and then discusses and analyses the criteria that governed and shaped the final destination of each pathway.

Security-Bureaucratic Procedures

After arrest by a security agency, the detainee was transferred to one of the main branches or sections of that agency in his city or town, or to Damascus. After the branch’s customary “welcome party” [torture], the prisoners were distributed to the cells and internal sections of the branch. Each section controlled several cells and interrogation offices, their number varying with the size and importance of the section and of the branch itself.

Once inside the branch and once the detainee was registered, the security interrogation phase began either immediately or after a delay. It could last a few days, several months, or, in some cases, more than a year. During this time the prisoner was subjected to severe physical and psychological humiliation and torture, and was deprived of food and medical care. The prisoner sometimes died as a result. In most cases the family had no idea where he was, making the detention a clear case of enforced disappearance.

These interrogations and the accompanying punitive measures took place outside any clear legal framework. They served as a security tool to extract confessions that would later be inserted into the “security file,” known procedurally as the “investigation dossier”, which determined the subsequent referral route — to a court, another security branch, the Military Police, or another body — and therefore the prisoner’s ultimate fate.

According to field testimonies and local and international human-rights reports, confessions were extracted — even in minor cases — under torture, through a variety of methods and threats that could include rape, its simulated threat, or even killing. The prisoner was then forced to sign papers whose contents he did not know. Those confessions taken during interrogation formed the core of the “investigation dossier” and provide the first glimpse of how the security agencies encroach upon the judiciary: by compiling the “investigation dossier”, the agencies exercise quasi-judicial powers, especially in “describing” the prisoner’s acts, deciding which body will handle the case, or even deciding his fate in the branches.

This encroachment by the security agencies upon the judiciary emerged not only in the outcomes of later trials, but from the very first moment of detention. Security interrogators drafted the charge and interrogation records and recommended the referral; the files then followed an internal administrative–bureaucratic circuit inside the security agency and the high-level departments linked to it, before they were sent directly to the competent judicial, military, or civil bodies.

In this context, the research team reviewed several leaked confidential files from the Air Force Intelligence Directorate and the Military Intelligence Division. These files contained data on more than one hundred thousand prisoners and their referrals (under interrogation – referred) from the start of the Syrian Revolution until 2017.(28) After verifying and cross-checking the data, it became clear that, at the end of the interrogation stage, the responsible interrogator issued a recommendation that determined the prisoner’s fate and the body to which he should be referred. That recommendation was not implemented immediately; it was first sent to the Head of the Interrogation Section, who reviewed or amended it, then was forwarded to the Head of the Security Branch, who added his opinion, amended, or approved it, and recorded it in the “Brigadier General Branch Chief Proposal”. The file was then forwarded to the Director of the relevant security agency—for example, the Director of the Air Force Intelligence Directorate.

Later, once the dossier had reached the leadership of the agency in charge of the branch, the “Major General” issued the final decision approving or modifying the referral. The decision then went to the National Security Office and was attached to an official memorandum bearing a number and date; at this point the referral acquired executive force, and the prisoner was transferred to the judicial body specified in the final memorandum based on the recommendation—whether the military judiciary, the Terrorism Court, the Military Field Court, or even the civil judiciary—without any recourse to an independent judicial authority. It should be noted that referral to certain military-judicial bodies, such as the Military Field Court, may have required the signature of the Minister of Defense, as was observed in the referrals issued by the Air Force Intelligence Directorate and the Military Intelligence Division.

Regardless of the final judicial body to which the prisoner was referred, it is plainly evident that the referral files issued by the security agencies were treated by the judicial authorities as conclusive evidence that was neither reviewed nor examined, and they were often not even shown to the defendant or to his lawyer (Field Courts did not allow lawyers). This administrative–security architecture “cast a legal veneer over purely arbitrary procedures,” and helped to disappear tens of thousands of civilians in the “human slaughterhouses” of the security branches or in Sednaya Military Prison, leaving no official legal trace of their detention that their families could readily obtain.(29)

Referral Destination: Potential Pathways

The interrogation dossier—with its catalogue of charges and extracted confessions, the interrogators’ recommendations, and the endorsements of branch and security-agency chiefs—constituted the decisive factor in charting the prisoner’s referral path to the body that would determine his fate, provided he survived this journey and did not perish in the security branches. The prisoner remained in the branch cells until the cycle of procedures relating to his file was completed, a cycle in which he was never a party. He was merely a dossier moving through an inexorable security-bureaucratic process that had to run its course whether its subject was dead or alive.

The referral decision issued by the security agencies sketched several possibilities for the prisoner’s subsequent path, possibilities that depended on a variety of factors—case type, charges, extracted confessions, and the nature and considerations of the security agency—but that ultimately converged on a limited set of pathways.

To map those pathways and their destinations, the research team, drawing on field interviews and a review of relevant reports and studies, examined leaked files from the Air Force Intelligence Directorate and the Military Intelligence Division, which contained data on more than one hundred thousand prisoners and their referrals.(30) The aim was to trace the potential routes by which civilian detainees were transferred from the security branches and to identify the principal civilian, military, or judicial bodies to which they were sent, bodies that in most cases served as transit corridors leading to Sednaya Military Prison. Accordingly, the prisoners’ referral routes out of the security apparatus were distributed across the following approximate possibilities:

Referral to the Military Field Court

The Military Field Court was one of the most dangerous exceptional courts in the military judiciary. It was established by Legislative Decree No. 109 of 1968 (31) to be used in times of war and emergency military operations, and it was originally competent to try military personnel. Hafez al-Assad later expanded its jurisdiction through Legislative Decree No. 32 of 1980, which empowered the court to hear cases arising from “internal unrest,”(32) thereby allowing wide segments of civilians to be brought before it.

During the first years of the Syrian Revolution, the criteria and policies by which the security agencies referred cases to the Military Field Court were not clearly defined. Gradually, however, referrals focused more on matters linked to the armed uprising, and the court was employed heavily after 2011. This trend is underscored by the regime’s creation, in 2012, of a second Field Court chamber to cope with the growing number of prisoners sent there.(33)

All four principal security agencies adopted—though to differing degrees—the policy of referring large numbers of prisoners to the Field Court. In some branches, a committee was formed to interview those being sent to the Military Field Court, and another committee met those returned from the courts, since in some cases a prisoner was transferred back from another court, such as the Terrorism Court, before being sent on to the Military Field Court, or vice versa. According to the referral files reviewed by the research team, in only two very rare instances did the Military Field Court itself request that interrogation be repeated for two prisoners (brothers), without explaining the reason.(34) This demonstrates that the court relied on the interrogation dossier forwarded by the security agencies as final, without re-examining it.

The Military Field Court served only to give a formal-legal veneer to the security agencies’ decisions to liquidate prisoners. It usually issued death sentences or life imprisonment inside Sednaya Military Prison without informing the prisoner or his family. The sentence would later be carried out at Sednaya, or the prisoner would simply be left vulnerable to liquidation while serving his term in the same prison. The court continued to operate until it was abolished in September 2023.(35)

According to the Syrian Network for Human Rights, the Military Field Courts issued at least 14,843 death sentences between March 2011 and August 2023. Of these, no fewer than 6,971 sentences were commuted to temporary or life imprisonment with hard labor—most while the prisoners were already in detention centers during the documentation period. The death penalty was nevertheless carried out against another 7,872 people, including 114 children, 26 women, and 2,021 military personnel. None of the bodies were returned, and the families were never officially informed. The Network believes this figure represents only the minimum number of executions that actually took place against prisoners and the forcibly disappeared in Assad-regime detention centers.(36)

Referral to the Terrorism Court

The Terrorism Cases Court was created as the successor to the exceptional State Security Court by Law No. 22 of 2012,(37) following the promulgation of Counter-Terrorism Law No. 19 of 2012,(38) more than a year after the State Security Court had been abolished. The court was supposed to hear offences related to “counter-terrorism”, yet this legal notion remained fluid and overly broad, allowing the authorities to criminalise any form of opposition including peaceful activism. Under its provisions, tens of thousands of cases were tried for actions such as demonstrations, distributing leaflets, journalistic documentation, human-rights work, or even providing first aid to demonstrators.(39)

From 2012 onward, referrals by the various security agencies to the Terrorism Court became a common pathway, especially for civilian activists — including media workers, relief volunteers, and unarmed demonstrators. The prisoner was first sent to the court’s special prosecution office, then brought before an examining judge who had no power to review the security interrogation dossier and relied entirely on the records of the security branches, with no independent inquiry.

The court usually rejected motions for release without providing reasons and conducted perfunctory interrogation sessions during which ready-made charges were read out to the prisoners. In most cases, lawyers were barred from consulting their clients’ files or mounting a real defence. In some proceedings, lawyers acted as intermediaries between the prisoner’s family and the judge to pay a financial ransom in exchange for a lighter sentence or release. Ultimately, the case was transferred to a felony judge within the Terrorism Court, where the accused was sentenced.

Leaked regime archives, reports by the Association of Detainees and Missing in Sednaya Prison, and field testimonies indicate that the Terrorism Court was a principal conduit for sending prisoners to Sednaya Military Prison — though less so than the Military Field Court — after trying them not only under the Counter-Terrorism Law but under all applicable penal statutes, including the General Penal Law. The court also referred thousands of prisoners to other prisons while keeping others in open-ended detention for years without trial.(40)

A 2020 report by the Syrian Network for Human Rights documented that the Terrorism Court had heard 90,560 cases since its establishment. The report added that 10,766 defendants — including 896 women and 16 children — were still on trial at that time. The court had issued at least 20,641 prison sentences and at least 2,147 death sentences, most of them in absentia, in addition to 3,970 property-seizure orders.(41)

Referral to the Military Judiciary

Although Syrian law states that civilians must not be tried before the Military Judiciary except in narrowly defined circumstances, the Military Judiciary was used for decades as a means of prosecuting civilian activists and politicians—especially during the years of the revolution—on the basis of referrals from intelligence branches rather than criminal evidence or proper legal procedure. Its broad jurisdiction enabled it to try wide segments of the civilian population and to choose whichever legal framework it preferred, drawing not only on the Military Penal Law but also on provisions of the General Penal Law and other laws, particularly those criminalizing offenses against public authority, including insulting the President of the Republic.

That breadth of legal authority was often invoked as a pretext to refer civilians to military courts outside their natural jurisdiction, turning the Judiciary into an exceptional judicial authority for political and security purposes. The Independent International Commission of Inquiry reported that the military courts “acted as a direct extension of the intelligence services, issuing verdicts based on secret security reports and confessions extracted under torture,” a finding also confirmed by Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch.(42)

Because judicial jurisdictions overlapped, some prisoners’ cases were referred to the Military Judiciary from the outset. If the court later acquitted them of charges with a military character, the case was transferred to the civil judiciary to consider any remaining charges.

Referral to the Civil Judiciary

During the first months of the Revolution, and in specific cases—or when the charge was clearly non-political—the prisoner was referred to the Public Prosecutor’s Office or to an Investigative Judge within the civil judiciary. A case file was opened, and procedural guarantees such as legal representation and a public trial were available, at least in theory. This pathway was common before 2012 for certain individual protest cases, or for women and elderly prisoners in non-“security” cases, and it usually ended in release or in transfer to civil prisons if a prison sentence was imposed.

Conversely, the civil judiciary had the authority to issue death sentences for some crimes, especially those that the law classified as “extremely serious,” such as premeditated murder or acts linked to “terrorism”. Civil Felony Courts normally had jurisdiction over these cases and issued their judgments after public hearings that were supposed to respect fair-trial guarantees, yet those guarantees were frequently violated in practice. The Syrian Network for Human Rights documented, between April 2019 and July 2020, 58 death sentences, along with other rulings of imprisonment, detention with hard labor, and civil disenfranchisement against 80 persons; most of the judgments were based on charges related to “terrorism.”(43)

Referral to Another Security Branch

In certain cases, a prisoner was not transferred directly to a court; instead, he may have been referred to one or more additional security branches without any legal settlement. Witness statements and human-rights reports indicate that shuttling between different branches—during or after the end of interrogations—was common. For example, a prisoner might start his journey in Air Force Intelligence, then be moved to the Interrogation Branch 248, and later to the Palestine Branch 235 or elsewhere. Such referrals were usually linked to questions of branch authority and geographic scope, the desire to extract additional “confessions,” or they overlapped with other cases or persons handled by those branches.

Throughout these forced transfers, each branch repeated its own procedures of interrogation and torture. The transfers could last for several months or, in rare cases, for years, and sometimes involved multiple branches. According to a report by the Association of Detainees and Missing in Sednaya Prison that examined a sample of 400 prisoners sent to Sednaya Military Prison, 41.47% of the sample passed through at least two security branches before reaching Sednaya, while 30.71% went through one branch, 22.57% through three branches, and 6% through four or more branches belonging to different security services. (44)

It should be noted that provincial security branches did not have the authority to refer prisoners directly to Sednaya Military Prison. The transfer had to be carried out by the central branches of the various intelligence services. Consequently, it was normal for a prisoner from a governorate other than Damascus or Rural Damascus to pass through at least two branches, whereas some prisoners returned to the first branch after passing through three or four others.

During these transfers, the prisoner was not a party to any fair legal procedure; rather, he became the target of several agencies and a test subject for overlapping security practices. The process began with systematic torture and medical neglect that could lead to death inside a branch, or with a recommendation—based on “extracted” confessions—that ultimately sealed his fate before one of the military or exceptional courts.

Referral Directly to Sednaya Prison

In some cases, because the Security Branches were overwhelmed by the large number of prisoners or because the Field Court, the Terrorism Court, and other military courts were burdened with too many files, prisoners were dispatched straight to Sednaya Prison without trial, to await appearance before the competent court. This practice resembled depositing the prisoner in the prison on the Branch’s behalf until the case file—especially when tangled and complex—was completed.

Later, the prisoners were moved from Sednaya Prison to the competent court and then returned under harsh, inhuman conditions. They were usually transported in sealed trucks known as “meat freezers” or in small white minibuses, and throughout the journey their hands were shackled and their eyes blindfolded. The trips between the court and the prison sometimes passed through Tishreen Military Hospital, where corpses were loaded into or unloaded from the same vehicles, intensifying the psychological and physical torment experienced by the living prisoners in transit.(45)

Referral to a Military Hospital

Rarely did a prisoner inside the security branches receive a medical check-up or see a forensic doctor, even in cases of severe injury. On occasion, the branch’s own doctor was summoned—the majority of branches contained a medical section called the clinical section. When the prisoner’s health deteriorated sharply because of torture or medical neglect, he may have been sent to one of the military hospitals.

The transfer decision was issued only with security approval from the interrogation officer and/or the head of the branch, and usually only after the condition had worsened to the point of endangering the prisoner’s life. The move functioned as a temporary measure to slow physical collapse, not to save the prisoner’s life,(46) especially when the branch wished to keep him alive—to extract further confessions, because relatives had paid bribes, or, in rare cases, because he may have proved useful in later negotiations.

The prisoner was transported to the hospital shackled, escorted by Military Police personnel and/or agents from the detaining security branch, and confined in a wing reserved for prisoners under conditions little different from prison itself: under tight guard, with no visits, and constant surveillance. Testimonies indicate that many prisoners received no real treatment; only rudimentary steps kept them briefly alive. Some were beaten even while in the hospital bed and were denied painkillers or proper care, making the referral a tool for delaying death rather than saving life. Once the condition partly improved—or merely stabilised in the eyes of the security team—the prisoner was returned to the branch and often subjected at once to fresh interrogation sessions that involved further torture.(47)

The Death Path: Referral of Corpses and Files

Facing all the possible pathways open to prisoners inside the security branches—and the systematic medical neglect, psychological torment, and physical torture they endured—death appeared to be one of the most likely outcomes. Field testimonies and human rights reports indicate that the vast majority of prisoners died inside detention centers run by the security agencies before their case files could enter any of the previously described pathways. The causes ranged from torture and lack of medical care to direct liquidation inside or outside the branch (the Tadamon Massacre is a stark example). The bodies—or, at times, only their files and numbers—were then “referred” through a chain of security-medical procedures designed to erase the crime’s traces and provide a false veneer of officialdom to the death.

If a prisoner died inside a security branch, the first step was to record the death in the branch log. Orders then followed to transfer the corpse to a military hospital—most often Tishreen Military Hospital—using military vehicles or under Military Police escort.(48) Once the body reached the hospital detention room, a Military Police detachment received it, registered it in their ledgers, and placed it in a separate unit without any genuine forensic-medical examination to determine the true cause of death.

Next, the hospital’s forensic department issued a perfunctory death report citing fabricated medical reasons such as “renal failure” or “cardiac arrest,” with no criminal inquiry or independent autopsy. Military Police documented and photographed the body according to a set protocol. These reports were later used to register the death in the Directorate of Military Records and then in the civil registry, without disclosing the responsible party or the real circumstances of death.(49)

Afterward, the corpses were loaded into sealed vehicles and transported to mass graves—especially in the areas of Najha, Qutayfa, Set Zaynab, and elsewhere. A special security detachment coordinated the transfer with the Damascus Burial Office, which was administratively subordinate to the Damascus Governorate. In some cases, a belated official notice was sent to the prisoner’s family through the neighborhood mukhtar [headman] or the Military Police, stating that the prisoner had died but providing no details about the cause or the whereabouts of the body.

In other instances—particularly after 2015—deaths were recorded inside the security branch itself, and the bodies were transferred directly to the mass graves. The branch merely sent a list of the deceased to Tishreen Military Hospital so that the hospital could draft death reports and issue death certificates in accordance with the branch’s records. If the death occurred inside the hospital,(50) the Military Police wrote up the judicial report and forwarded it to the Directorate of Military Police, which then dispatched an investigator, a single military judge, and a forensic doctor to confirm the death. All remaining procedures followed the same pattern outlined above.(51)

Referral to the Military Police

The Military Police in Syria could form an independent pathway within the detention network, especially when a prisoner was cleared of security charges but was classified as wanted for compulsory or reserve military service. In such cases, the referral note typically stated, “Refer the person(s) in question to the Military Police Branch in Damascus so that he/they may be inducted into compulsory or reserve service, or have his/their conscription status regularized,” as appropriate.

In other situations, the Military Police served as a mandatory corridor that intersected nearly all security pathways leading to Sednaya Prison or other facilities. Prisoners were often transferred to the Military Police after leaving the security branches, either for re-classification or for another transfer to a detention center. This transfer constituted a transitional stage that could occur more than once, and the time spent there was used to apply additional psychological or physical pressure.

The 2014 “Caesar” leak of 55,000 photographs revealed thousands of corpses that the Military Police had been tasked with numbering and matching to their security files, underscoring the central role of this body in the machinery of systematic killing. United Nations and human rights reports indicate that the vast majority of prisoners who died in security centers ended their journey with the Military Police, who photographed and registered their bodies before burying them in mass graves. Thus, the Military Police were not merely an administrative body; they were an organic extension of the repressive structure that perpetuated cycles of detention, torture, and enforced disappearance.

Several human rights reports have documented systematic torture inside Military Police headquarters and their affiliated detention sites, particularly at their headquarters and prison in the Qaboun district of Damascus. That complex functioned as a hub for data collection, coordination of transfers among prisons, and storage of victims’ records, while withholding clear information from families. When relatives inquired about a prisoner’s fate, they were often told at the Qaboun Branch that their loved one had died, and were instructed to go to Tishreen Military Hospital to obtain a death certificate. In some cases, the Military Police send official telegrams to families, local authorities/mukhtar [headman], or civil-status offices to notify them of the death. In every scenario, however, the process stopped short of handing over the body because of the security procedures in force.(52)

Other Potential Pathways

Some referrals moved beyond their judicial character and assumed a security-negotiation dimension. Certain prisoners were returned to the security branches so that their presence could later be used in bargaining files or exploited for political or security leverage. A review of referrals issued by the Air Force Intelligence Directorate and the Military Intelligence Division shows that the remarks column sometimes read “subject for negotiation”, clearly signaling that the referral was being used as a pressure tool. For example—and especially in the file of female prisoners—the Terrorism Court may have been asked to return the prisoner to the branch after she had completed her sentence so that she could be exploited in a future negotiation.(53)

The data naturally reveal both individual and collective referrals, in which several prisoners are referred under a single case file. This pattern is evident in files that state “all of them” or list multiple names under one dossier number, and it is usually tied to collective accusations such as “membership in an armed group” or “planning a terrorist act”.

Within this pattern, the group was sometimes treated as a single unit—without distinguishing their individual circumstances—and thus referred to the same judicial authority; or the referral pathways may have diverged for each of them according to the course of the interrogation. For example, within the same dossier, some prisoners may have been slated for referral to the Military Field Court, others to the Terrorism Court, others to various other pathways, and still others may have been released.(54)

Factors Influencing Referral Pathways (Qualitative Criteria)

As clear as the possible pathways for referring prisoners from the security branches may seem—especially those leading to Sednaya Military Prison—the task of defining the criteria for referral to the judiciary in its various forms, whether military, exceptional, or civil, remains problematic and somewhat obscure, even after the fall of the Assad regime. Although a nominal “legal” framework was supposed to govern the choice of one pathway over another, actual practice during the Syrian Revolution deviated systematically toward a coercive security-political logic that reduced legal standards to a mere façade for decisions often taken by the security agencies according to their own unmonitored criteria.

In this context, field interviews, leaked documents, and relevant studies and reports indicate that a set of factors could decisively alter the final destination of a referral—thus tipping the balance toward one pathway rather than another and ultimately determining the prisoner’s fate. The most prominent of these factors were:

The Nature of the Security Agency

Referrals issued by the security agencies showed a clear divergence in their ultimate destination. Those coming from the Military Intelligence Division and the Air Force Intelligence Directorate usually led to the harshest pathways, above all to the Military Field Court and the Terrorism Court, which in turn meant an almost certain referral to Sednaya Military Prison. This outcome stemmed from the agencies’ military nature and command structure, together with their rigid ideological outlook, which linked security work directly to loyalty to the regime and to systematic violence against any potential opposition. Investigators in these branches often referred to prisoners under the highest level of “danger,” adding inflated security descriptions to justify sending them to Sednaya.

By contrast, referrals issued by the Directorate of General Intelligence or the Division of Political Security were less likely to end in Sednaya. In many cases, they sent prisoners to the civil judiciary or, in some instances, to the ordinary military judiciary—especially during the first years of the revolution, before the Terrorism Court was established in 2012.

This disparity can be attributed to the fact that the latter agencies, despite their repressive role, remained more connected to the state’s traditional administrative structure and were less immersed in the “total-war” mindset that prevailed inside the military agencies. The difference shows that a detainee’s fate was determined not only by his actions or the charges brought against him, but also by the nature of the security agency that arrested and interrogated him. According to the report Detention in Sednaya, which analysed a sample of 400 former prisoners in Sednaya Prison,(55) the detentions that ultimately led to Sednaya were distributed among the four principal security agencies as follows:

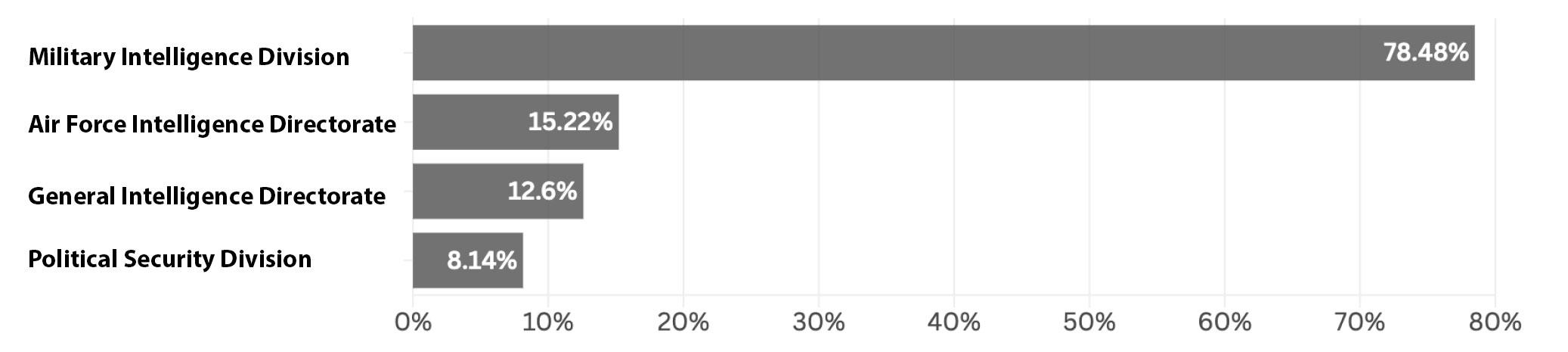

Figure 1. Distribution of 400 former prisoners in Sednaya Prison, by the security agencies that detained them.

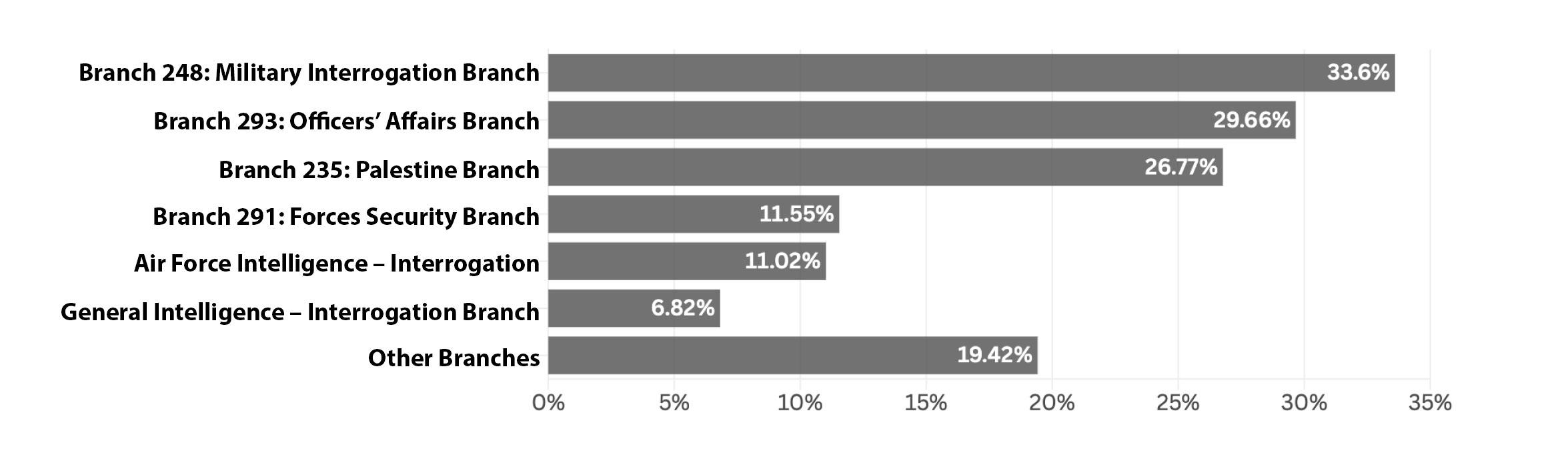

On the other hand, the presence of a primary Interrogation Branch within every Syrian security agency constituted a fixed structural feature that reflected the importance of interrogation as a central tool in the work of these agencies. Despite this uniform pattern, some security agencies retained additional particularities by creating specialized branches, such as the Palestine Branch, and the branches dedicated to Officers Affairs and Force Security within the Division of Military Intelligence. Consequently, the sample for the report Detention in Sednaya(56) highlights both the danger posed by the central Interrogation Branches of the security agencies and their position at the top of the transfer hierarchy, while also showing transfers from other central branches such as the Palestine Branch or the Officers Affairs Branch. The sample was distributed according to the branches that most frequently transferred prisoners to Sednaya Prison, as follows:

Figure 2. Distribution of four hundred former prisoners in Sednaya Prison, by the security branches that referred them there.

Nature of Charges and Extracted Confessions

Confessions extracted under torture or pressure became one of the main determinants of the referral pathway. The referral did not rely solely on legal texts or judicial jurisdiction; instead, it was driven by the content of the confessions and the recommendations of the interrogator. These recommendations, usually recorded in the interrogation reports, often decided the prisoner’s final referral route.

Over time—and as prisoner numbers increased—the wording of extracted confessions began to function as a kind of reference code that told the court, or the body to which the prisoner would be referred, what final fate and sentence were required. For example, inserting the phrase “attacking army and security checkpoints and opening fire on them” is enough to divert the file to the Military Field Court, implicitly instructing that court to impose the death penalty on the prisoner when he is brought before it.(57)

A review of more than 100,000 referrals shows that the security agencies did not refer prisoners according to the Penal Law articles in any clear way. Instead, they relied on the extracted confessions and/or on items seized with the prisoner (weapons, ammunition, money, etc.). The referral path was therefore set according to what the security agencies deemed an appropriate description of the case, not according to rules of judicial jurisdiction.

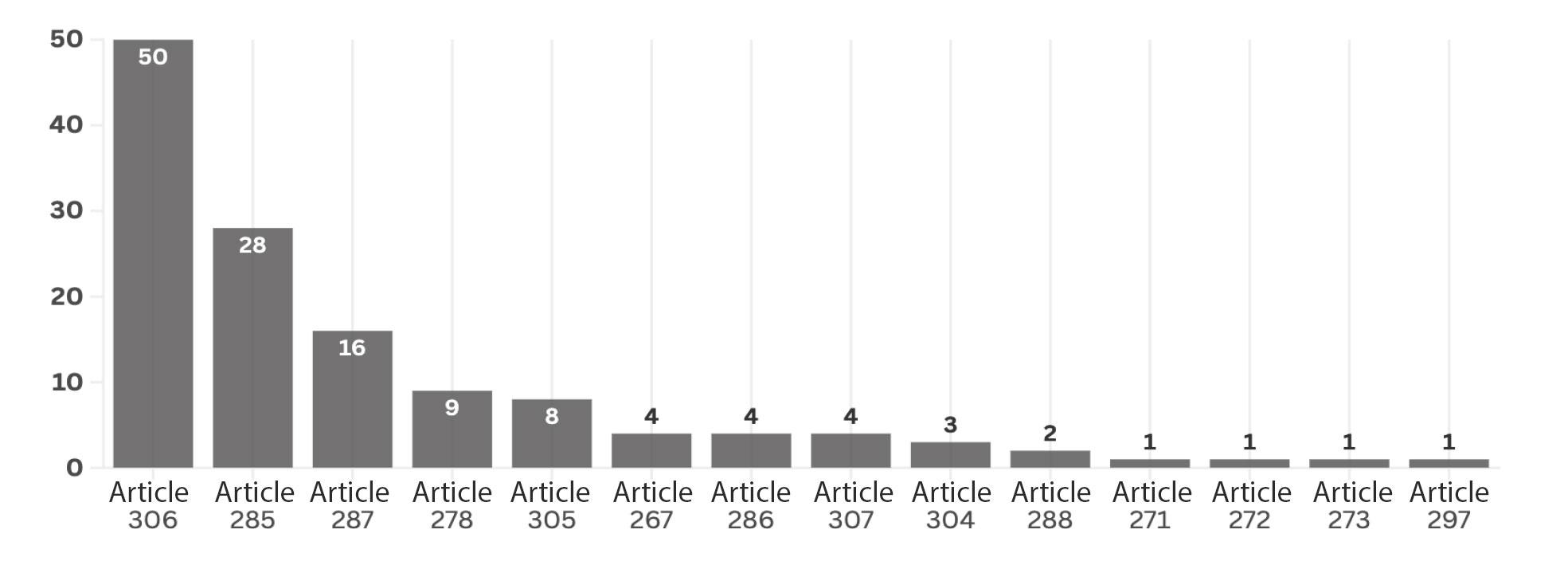

In the courts, articles from the Penal Law, the Military Penal Law, and the Terrorism Law were used interchangeably as legal references to match the charges attached by the security agencies. In most cases, the prisoner did not know what charges the interrogator had inserted in the final interrogation dossier, and therefore did not know under which legal articles he was tried—especially when referred to the Military Field Court, and to a lesser extent the Terrorism Court, followed by the Military Judiciary. According to the report Detention in Sednaya, out of a sample of 400 cases, only 132 prisoners were able to point to a specific legal article used against them. Those articles were usually the ones related to “crimes against state security and public safety” (articles 260 to 339) of the Penal Law.(58)

Figure 3. Charges that 132 of the 400 former prisoners of Sednaya Prison were able to identify, and on which they were tried.

Sectarian Affiliation

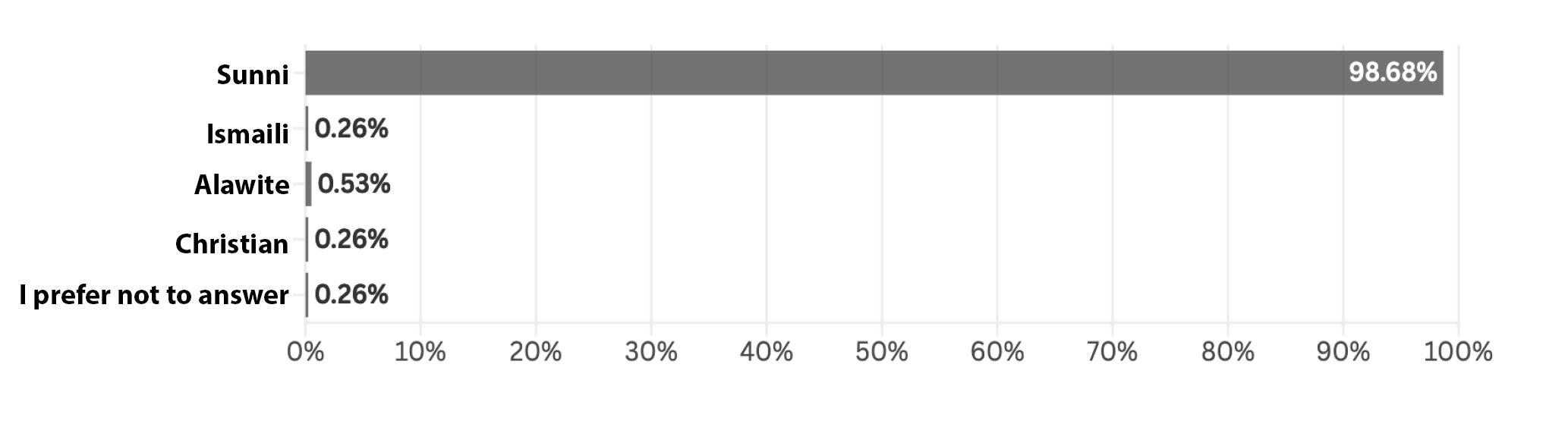

Sectarian affiliation often shaped the prisoner-referral pathway. Legal standards or the nature of the charge were seldom the only factors that decided a prisoner’s fate; the sectarian background of both the interrogator and the prisoner frequently mattered as well. In an internally unbalanced security apparatus, many interrogators dealt with Sunni prisoners in an overtly punitive spirit, driven by a security mindset that automatically linked Sunni identity to opposition activity.

In this setting, the interrogator’s recommendation—attached to the prisoner’s file and steering the referral—depended not only on evidence or the alleged offense but also on sectarian bias. Thus, prisoners were sent to the Military Field Court or the Terrorism Court, judicial avenues that usually ended in Sednaya Prison. Even when no clear security or military evidence existed, pressure and torture were applied until the prisoner confessed to a charge crafted to justify a transfer to Sednaya. Referral became a systematic tool of sectarian discrimination, not a neutral legal procedure; at times, sectarian identity weighed more heavily than the act itself in determining detention, trial, and punishment.

This pattern aligns with the security architecture of the regime, which used sectarian profiling to re-engineer society and secure political loyalty. The exceptional judiciary served as a façade that legitimized discrimination instead of acting as an impartial arbiter between citizen and state. The report Detention in Sednaya underscores this reality: among a sample of 400 former prisoners in Sednaya Prison, sectarian distribution appeared as follows:

Figure 4: Sectarian distribution of a sample of 400 former prisoners in Sednaya Military Prison

Regional Affiliation

Regional affiliation—whether of the interrogator or the prisoner—was likewise a decisive factor in determining the referral pathway. Prisoners were never viewed in isolation from the geographical background to which they belonged. On the contrary, an interrogator’s behaviour was often shaped by security-service stereotypes that branded certain Syrian areas as “hotbeds of rebellion” or “incubators of chaos,” such as Idlib, Daraa, Homs, Douma and Daraya in the Damascus suburbs, and others. This politicisation of geography turned what should have been a judicial procedure into a tool of collective retaliation that extended beyond the individual to punish the prisoner’s entire local community, even when the individual was innocent.

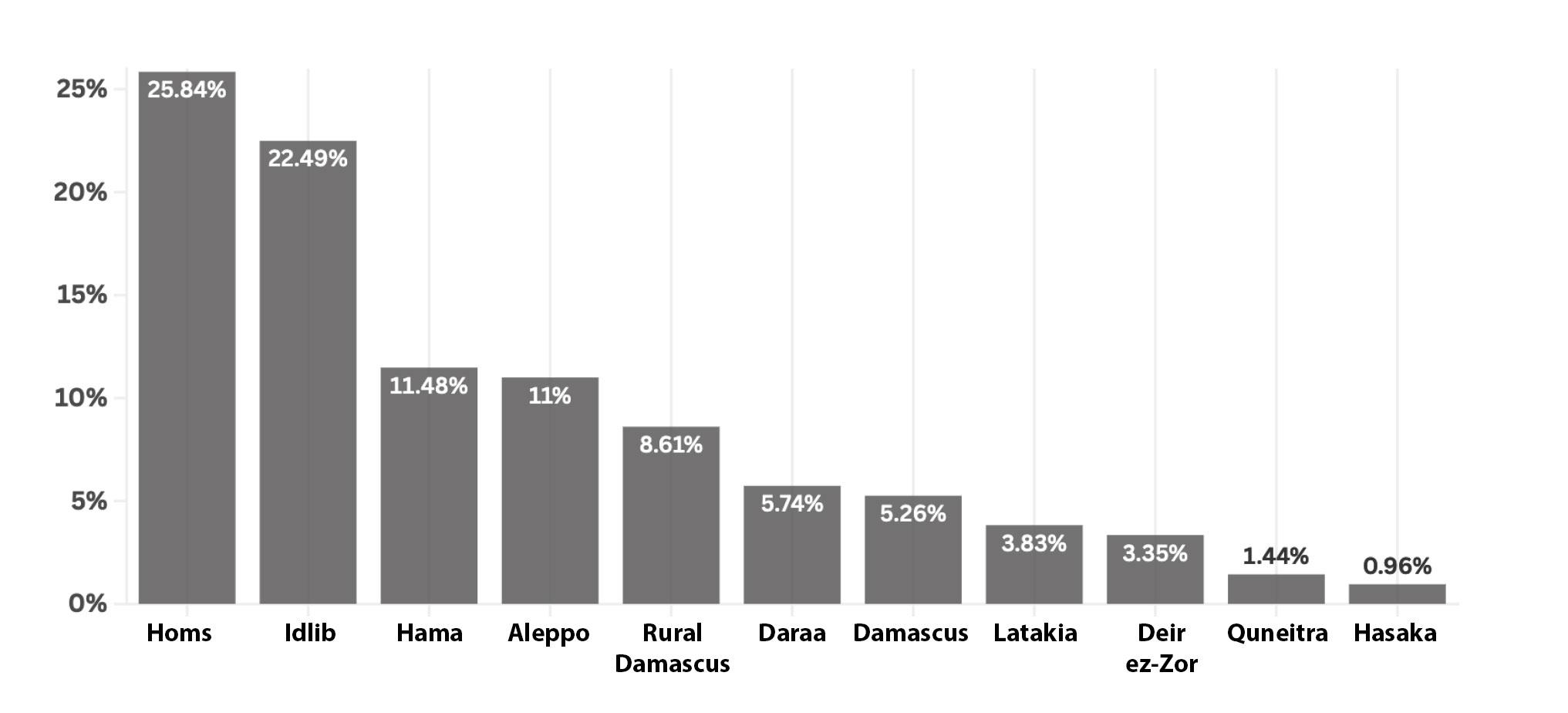

These perceptions—whether rooted in the interrogator’s personal bias or in broader institutional directives—directly affected referral recommendations. Files of prisoners hailing from specific areas were routinely channelled toward pathways that ended in Sednaya Military Prison. Geographic origin thus became an implicit charge parallel to any formal accusation, illustrating how the security-judicial system embraced vengeance rather than justice, and political punishment rather than legal accountability. The report Detention in Sednaya confirms this pattern, showing the post-2011 distribution of prisoners by governorate as follows:

Figure 5: Regional Distribution By Governorate For A Sample Of 400 Former Prisoners In Sednaya Prison

Corruption: Influence and Well-Timed Bribes

Connections or the payment of ransom could mean the difference between life and death for the prisoner, especially during the interrogation stage in the security branches, where the course of judicial referral was redrawn according to the amount of influence or the ability to produce money at precisely the right moment. Testimonies from former prisoners and defectors from the security agencies confirm that the intervention of an influential figure — whether from inside the regime or through a network of intermediaries — or the payment of a sum to the interrogation officer, his assistants, or his subordinates could lead to a rewriting of the security dossier, softening the charges brought against the prisoner or even deleting incriminating elements from the interrogation records.

In such cases, the recommendation rested not on what the prisoner had or had not done, but on the capacity of his relatives or circle to reach power centers in the security apparatus. The charge could then be re-described to appear less serious from a security standpoint, or converted into an ordinary civil or military case, thereby blocking referral to the Field Court or the Terrorism Court and sparing the prisoner the near-certain fate of Sednaya Prison.

These unlawful practices expose the fragility of the security institution and how easily it could be subverted by clientelism, influence, and financial corruption. The same holds true for the judicial system, which shifted from a body meant to be neutral into a closed marketplace where exonerations were sold and escape routes were bought, while thousands of other prisoners were abandoned to their fate simply because they lacked connections or money.

III. Tracing the Paths: Judicial Gateways to Sednaya (Legal-Security Criteria)

If we set aside the civil courts as a possible final destination for referrals coming from the security branches, all the remaining judicial paths reviewed in the previous section functioned as near-certain gateways to Sednaya Military Prison.

Accordingly, this section traces the referral routes of civilian prisoners to the military and exceptional courts, by expanding on the powers, procedures, and rulings of those bodies as judicial gates to Sednaya. This effort clarifies the legal-judicial standards behind those judgments and deepens our understanding of the pathways leading to exceptional or military justice and their consequences. It also highlights the degree of coordination between security and judicial agencies in producing a legal-security pathway that ends in Sednaya Military Prison—whether as a site of long-term enforced disappearance or an execution camp.

Military Judiciary: Expanding Beyond the Law and Dismantling Justice

According to the Military Penal Law and the Law of Military Criminal Procedure, the original mandate of the Military Judiciary was to try soldiers and those treated as such, with narrowly defined exceptions for trying civilians. Over time, the Judiciary’s sweeping powers and multiple areas of jurisdiction normalized those exceptions, creating a dangerous shift that turned the institution—over decades—into a punitive apparatus aimed primarily at civilians, especially those accused of “opposing the regime” or “threatening state security”.

The authority of the Military Judiciary is not limited to the crimes listed in the Military Penal Law;(59) it also extends to the Compulsory Military Service Law and to other laws and decrees, including the General Penal Law. Detailing these powers helps explain the supposed “legal standards” used to refer a broad spectrum of civilian detainees to the Military Judiciary during the Syrian Revolution. These powers were distributed as follows:(60)

Territorial Jurisdiction

Territorial jurisdiction of the military courts was defined by the decree that established each court, as stipulated in Article 45 of the Military Penal Law. That decree designated the court’s area of operation, and could later be amended by a subsequent decree. Under Article 46, this jurisdiction was broadened in times of war or internal unrest to cover any territory occupied by the Syrian Army, or any other area named in the formation decree.

Public right actions were filed before the judicial authority attached to the place where the crime was committed, the defendant’s domicile, or the place of arrest. Continuous or successive offences were deemed to have occurred in every location where their constituent acts appear. If the offence was committed abroad and the perpetrator had no residence in Syria, the action was brought in the capital.

Personal Jurisdiction

The personal jurisdiction of the Military Judiciary was set out in Article 50 of the Military Penal Law, which vested it with wide authority extending not only to service members on active duty but also to retirees, reservists, Ministry of Defense employees, prisoners of war, students of military schools and colleges, and anyone belonging to a military force constituted by decision of the competent authority, in addition to civilians who committed acts harming the interests of the army or who participated with service members in joint offenses.

In 2023 Bashar al-Assad issued Law No. 29, amending Article 50 of the Military Penal Law. The amendment required that the civilians covered by this article were tried before the ordinary criminal judiciary instead of the Military Judiciary, unless the offense arose from the performance of their official function, while retaining the possibility of referring a civilian to military courts if the offense was committed against a military member.(61)

Subject Matter Jurisdiction

The scope of subject-matter jurisdiction of the Military Judiciary extended to multiple categories of offences, as set out in Article 47 of the Military Penal Law. It covered, first and foremost, the strictly military offences defined in that Law and any other crimes committed directly against the interests of the army, regardless of the perpetrator’s status, whether military or civilian.

This jurisdiction also enabled the Military Judiciary to hear a wide range of offences listed in the General Penal Law(62)—especially crimes against public authority from Article 369 to Article 387. These included insulting or defaming the Head of State; insulting or defaming public administrations, regulatory bodies, the army, or an employee because of his position; and the offences classified under “State Security” and “Public Safety” from Article 260 to Article 339. Among them are: undermining the “prestige of the State” or “national sentiment,” joining an international political or social association without government permission, inciting sectarian or racial hatred, infringing civil rights and duties, belonging to secret associations, participating in demonstrations and riotous gatherings, arson, attacks on the safety of roads and transportation, and cutting telephone or telegraph communications.

Nor were those powers confined to the above. Under Article 51 of the Military Penal Law, the Military Judiciary took precedence in determining jurisdiction and venue; in other words, the military judicial authority itself decided whether a case fell within its remit.(63) It is also noteworthy that the martial governor and his deputies possessed exceptional authority to refer “State Security” cases to the State Security Court, even when a military party was already involved in the case.(64)

Once the prisoner was referred to the Military Judiciary, a case file was usually opened, and procedural safeguards such as legal representation and a public hearing were, in theory, available. However, the Military Court could—by law—decide to conduct the proceedings in secret, although the verdict had, in all circumstances, to be pronounced publicly. The Military Court could likewise ban publication of the hearing’s proceedings, or any summary thereof, if it deemed the matter to require such a measure.