Syrian Armed Forces Deployment: Point of No Return

The Syrian armed forces deployment strategy matches an emerging strategic threat and makes a return to the barracks unlikely.

Since the start of Syria’s civil war in 2011, the country’s armed forces—including ground force units, or the army—have undergone major strategic and tactical changes. Despite the fact that several years have passed since Russia- and Iran-backed loyalist forces succeeded in seizing back large swaths of territory from opposition forces, the army remains widely deployed in areas far from the front lines. It appears that Syria’s political leadership has adopted a new deployment strategy to fit the emerging threat of pockets of armed conflict or even popular revolt against the ruling political order. This strategy presents many risks and challenges. In particular, it addresses little beyond the desires of the political leadership, and will likely undermine international efforts to seek a political solution and return stability to Syria.

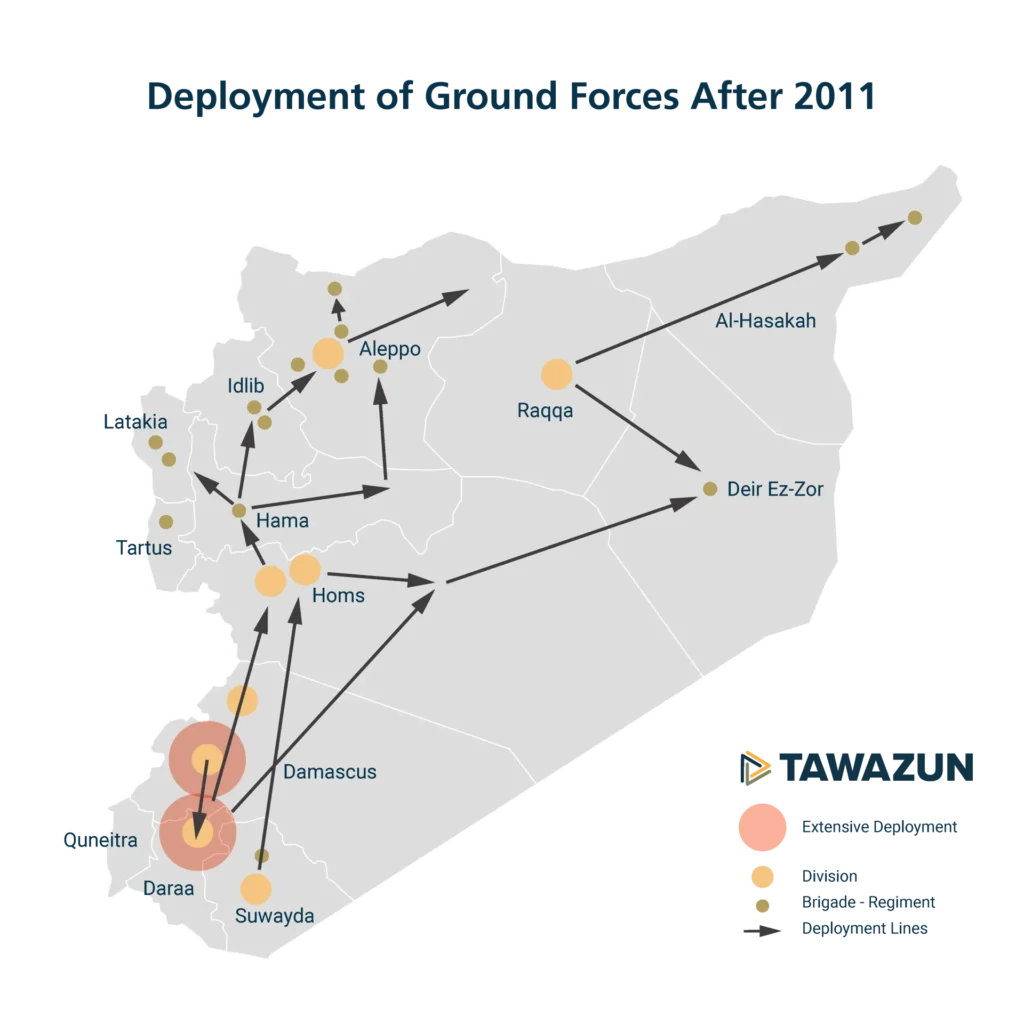

Post-2011 Deployment Errors

For decades, the strategic threat posed by Israel’s presence on Syria’s southwestern border, close to Damascus, was the key factor in army deployments in the south. This presence grew after former president Hafez al-Assad took power and established military and security units dedicated to protecting the ruling political order against coup attempts. Assad resorted to deploying special forces units and establishing barracks in some parts of the country, trusting these units to deal with any unrest. This strategy collapsed in 2011, necessitating the deployment of a number of units to the north and east in order to extinguish the uprising, far from the areas where those units had traditionally been deployed.

In a strategy that made little sense at first, military commanders did not initially send entire units to these new areas of operation. Instead, they took a “consolidation” approach, combining units from different divisions or brigades with other security forces under the command of a trusted officer. This strategy was intended to prevent mass defections, and it worked: the majority of defections since have been on an individual basis.

After “Consolidation”

However, this approach created a hybrid, uncoordinated structure that resulted in huge losses due to weak or absent command and control. Confusion reduced the effectiveness of military operations, leading to the creation of hybrid units in an attempt to restructure forces on the basis of geography, in keeping with the situation on the ground. Some of these units withdrew, voluntarily or under military pressure, from outlying areas to consolidate forces in bases with particular strategic or tactical value. These bases provided an umbrella of mutual fire support until these tactics started to collapse in spring 2015, and ended entirely with Russia’s military intervention in favor of the ruling political order later that year.

The Russian intervention in September coincided with the creation of the 4th Corps. Despite Russia’s support, this new corps did not deliver the results for which Moscow had hoped. In November 2016, the 5th Corps was created under Russian guidance, with relatively generous incentives and salaries and Russia-supplied weapons. It did not follow the typical military corps structure, due to the prior shortage of both personnel and armaments. In parallel, Russia sponsored hybrid units made up of personnel from the security apparatus and the army, as well as from local Iran-backed militias. Even a number of opposition elements that had entered into reconciliation deals were subsumed into the 5th Corps. This fragmented and undermined trust in the armed forces, which suffered from multiple loyalties.

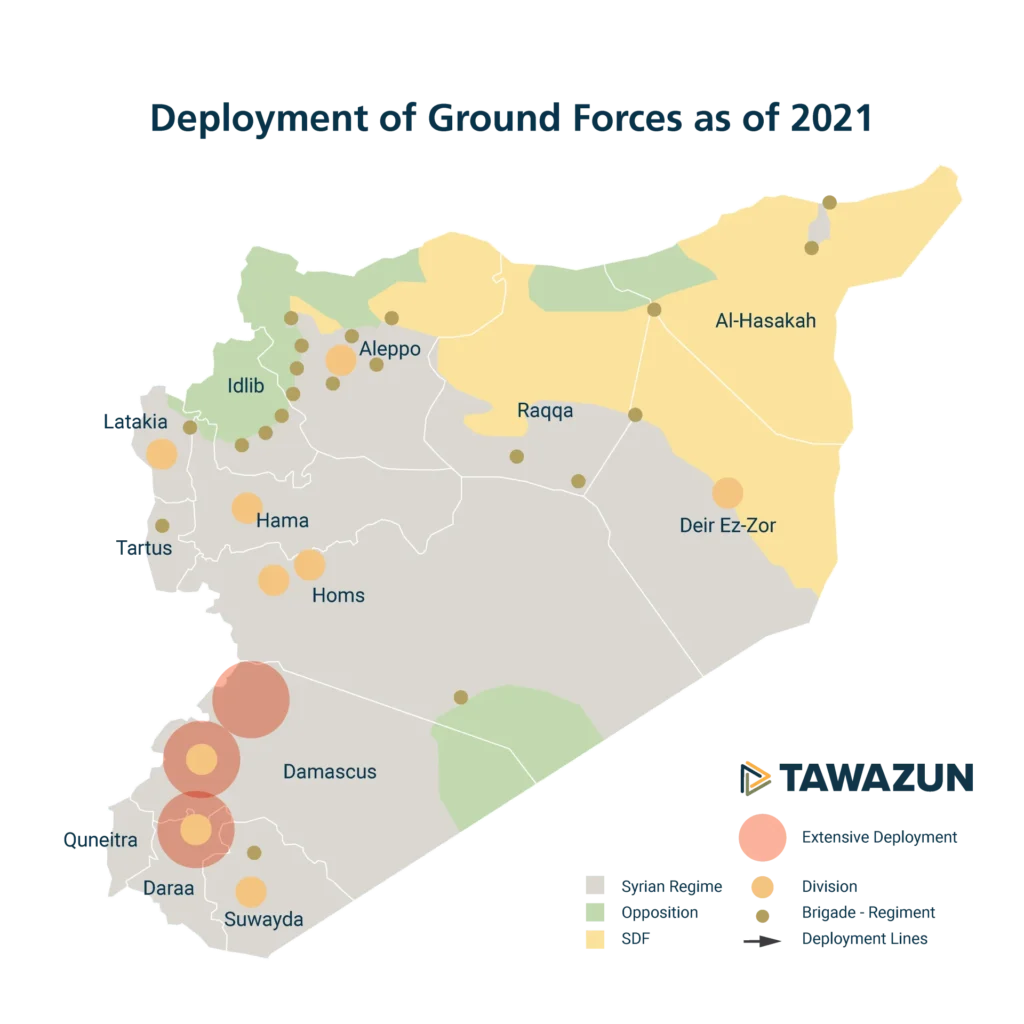

Current Deployments

Syrian army units have now been deployed in almost every city, town, and village under loyalist control for years, indicating that the army has no intention of withdrawing. Regardless of any political solution, the regime does not want to repeat previous mistakes in dealing with internal unrest. Furthermore, it is formulating a new strategy for deploying ground forces, sending units to each area with force sizes matching population density.

The Syrian armed forces’ deployment strategy is decided by the Military Defence Council, headed by the commander in chief—the president of the republic—without any involvement from civilian institutions. Given this, it is almost impossible to imagine the army returning to its previous, consolidated position, given that political leaders’ strategic outlook is now more internal than external. Furthermore, the Syrian army has been unable to replace heavy weaponry due to heavy losses and the government’s financial weakness. Furthermore, every future investment in logistics and equipment will be calculated through the lens of this new strategic threat, that is, prioritizing tools to suppress any future uprising. All this indicates that instability and the militarization of society will continue. It also threatens refugees’ opportunities to return. In particular, presumed political solutions have yet to touch on the question of the armed forces returning to the bases they left in 2011 to suppress the popular uprising in the first place.

Muhsen al-Mustafa is an assistant researcher focused on Syrian military institutions at the Program on Civil-Military Relations in Arab States at the Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center.