Syrian Amnesty Decree 27: Old Policy, No Progress

Key Messages

- Assad’s regime issued Legislative Decree No. 27 of 2024, mirroring past amnesty decrees but with additional wide exemptions.

- The decree excludes political detainees and prisoners of conscience, continuing a policy that neglects any political reform or reconciliation with opposition forces.

- Security agencies are not bound by the decree, limiting its impact and allowing them to detain individuals without judicial oversight, which reduces the practical effects of the amnesty.

- State security and Cybercrime offenses remain excluded, underscoring the regime’s intent to suppress dissent rather than promoting public safety.

- The decree fails to create a safe environment for the return of refugees and displaced persons as it does not address the root issues of security and political repression.

- The international community is urged to demand transparency and accountability from the regime to genuinely address detention and human rights abuses.

Background

On September 22, 2024, Bashar al-Assad issued Legislative Decree No. 27 of 2024,(1) granting a general amnesty for crimes committed before this date. This decree is the latest in a series of amnesty decrees issued by the regime, a trend that has accelerated since 2011.

Legislative Decree No. 27 closely mirrors the structure and legal provisions of the previous amnesty under Decree No. 24 of 2022(2)but introduces expanded exemptions to cover additional offenses and legislation enacted since 2022. It also varies slightly from the amnesty issued under Legislative Decree No. 36 of 2023.(3)

This analysis reviews the content and specific exemptions of Decree No. 27, examines its objectives and implications, and compares it with Decree No. 24 of 2022 to assess its continuity and changes within the broader pattern of Syrian amnesty policies.

A Routine Decree… Security Agencies as an Exception

The Syrian Penal Code classifies crimes into three categories: Violations are minor offenses punishable by a fine or imprisonment from 24 hours to 10 days. Misdemeanors carry penalties of imprisonment for 10 days to 3 years or a fine. Felonies are serious crimes punishable by death or imprisonment exceeding three years. This classification provides context for understanding the scope and limitations of the amnesty decree.(4) In general, any penalty with a minimum sentence of more than three years—whether imprisonment, detention, house arrest, or civil disenfranchisement—is considered criminal.(5)

Legislative Decree No. 27 of 2024 grants amnesty for all penalties related to misdemeanors and violations. It also includes amnesty for internal and external desertion, as defined in Articles 100 and 101 of the Military Penal Code. However, as with previous decrees, this one excludes individuals who remain in hiding or are fugitives unless they surrender within three months (for internal desertion) or four months (for external desertion).

The decree, however, exempts Articles 102 and 103 of the Military Penal Code, which address “defection to the enemy” and “conspiracy to defect,” both punishable by death. The regime classifies military personnel who defected to join opposition forces under these articles. Additionally, articles such as 137 through 150, which prescribe lengthy prison sentences or death penalties, remain outside the scope of this amnesty.

This exclusion underscores that the amnesty primarily targets military deserters who stayed loyal to the regime or reside in regime-controlled areas. Furthermore, the decree does not waive the exemption fee for individuals over 42 who did not complete military service, as this fee is considered civil compensation to the state. Similarly, compensatory fines under current laws are typically excluded from amnesty provisions.(6)

According to Article 3 of the Executive Instructions for the Civil Status Law, the amnesty waives fines for “all violations stipulated in the mentioned law and committed before September 22, 2024 of the legally required fines, provided they are settled within three months for those inside Syria and nine months for those abroad.”(7) While positive in theory, implementation remains challenging as Syrians outside regime-controlled areas, or those living abroad, face complex procedures in accessing Syrian diplomatic missions, often rendering this provision ineffective for them.(8)

In practice, individuals wanted by security agencies are excluded from amnesty benefits, as these agencies operate beyond legal and constitutional oversight. Public prosecutors do not visit security branches to determine if detainees qualify for amnesty, limiting their oversight to official prisons and detention centers.(9)The decree notably excludes political detainees and prisoners of conscience linked to opposition activities or political beliefs. Consequently, it fails to address the plight of most refugees and displaced individuals who fled Syria due to security concerns.

This is the third consecutive amnesty to exclude prisoners of conscience, limiting amnesty benefits to minor offenses and misdemeanors while leaving major charges intact. The regime’s disregard for this group underscores its unwillingness to make political concessions or engage in meaningful dialogue with the opposition.

Objectives and Dimensions of the Decree: Aims of Control and Security Regulation

Since 2011, the regime has regularly included desertion offenses in its amnesty decrees. By granting amnesty for desertion, it seeks to reintegrate deserters, particularly those in regime-controlled areas, back into its forces and to clear minor offenses for individuals who evaded or neglected mandatory or reserve service, though certain cases remain excluded.(10) However, this decree should not be mistaken for a genuine effort toward military restructuring or a shift to a “professional army,” as such reforms would require a national strategy involving cooperation across all Syrian factions. Such a strategy would need to encompass the following steps:

- Evaluating the regulatory legal framework and constitutional requirements for mobilization, conscription, and military service;

- Proposing legislative reforms for the military and security agencies, which currently operate outside constitutional and legal obligations, and instituting reforms within the military judiciary;

- Establishing independent civilian public institutions to oversee and monitor military reforms and transformation plans.

Regarding the potential impact of this decree on reconciliation dynamics, past settlements generally indicate that most officers who reached agreements with the regime were subsequently imprisoned and subjected to severe torture, not to mention being stripped of their civil rights. As for individual soldiers, in addition to being investigated, they are often forced back into the army, which remains a non-neutral entity. For most of those involved in reconciliation, the issue is not solely about personal safety; it is deeply tied to their national choices and stances.

By excluding crimes related to state security, corruption, and economic offenses from the decree, the regime signals its intention to maintain strict control and neutralize threats to its authority. Exempting cybercrimes, particularly those involving information technology, implies a stance of “protecting citizens” from digital threats, aligning with the regime’s recent crackdown on digital content creators and platforms it accuses of undermining societal values.(11)Additionally, the regime has leveraged the exclusion of cybercrimes to target its opponents, especially activists who have voiced criticism against the regime on social media, particularly in recent times.(12)

The regime’s continued disregard for political detainees and prisoners of conscience, whom it has detained throughout its rule—particularly since 2011—reflects its unwillingness to engage in any genuine political process or national reconciliation. This stance indicates a persistent policy of repression and restriction on fundamental freedoms, such as freedom of expression and peaceful assembly. The exclusion of political detainees even raises suspicions that some may no longer be alive, potentially having met their fate in mass graves.

Detention as a Persistent Indicator

The Assad regime continues to systematically obscure information and statistics related to detainees (providing neither data nor specialized institutions). Since the beginning of Ba’ath rule to the present day, the precise whereabouts of detainees remain unknown, and the regime has not officially disclosed the number of released detainees or their locations. This lack of transparency stems from the chaotic nature of information due to the dominance and multiplicity of security agencies, their conflicting operations, and lack of coordination. Additionally, the regime’s reluctance to disclose the real number of detainees aims to avoid using such data against it in human rights contexts. Politically, the regime seeks to keep this issue as a bargaining chip and tool for political leverage.

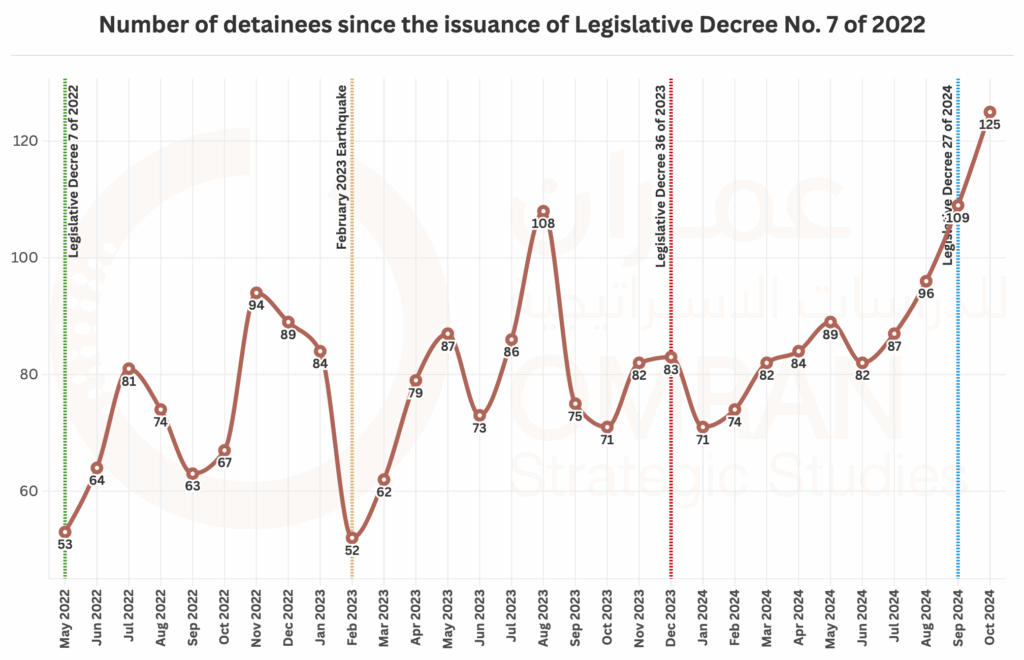

As of the release of this report, there is no official count of those released as a result of this amnesty, while legal sources estimate an increase in detention rates. In late April 2022, Bashar al-Assad issued Legislative Decree No. 7 of 2022,(13) At the time, it was considered “significant” for covering many offenses related to the Syrian revolution. However, it later became evident that the decree was largely symbolic, aimed at giving the impression that the regime was pursuing rehabilitation. In practice, repressive security practices continued, including arbitrary arrests, with the regime detaining 2,301 people by the end of September 2024.(14) Among them, 1,527 individuals were detained between the issuance of Legislative Decree No. 7 in 2022 and the issuance of Legislative Decree No. 36 in 2023, as follows:

Conclusion

The international community must intensify pressure on the Assad regime to disclose the fate of all political detainees and prisoners of conscience and work towards the release of those who remain imprisoned, and demand adherence to international human rights standards to end arbitrary arrests. Rather than accepting the regime’s amnesty decrees at face value, countries and organizations should critically examine these decrees with legal expertise, closely monitoring their implementation and insisting on transparency regarding actual beneficiaries. For the Syrian opposition, prioritizing the issue of detainees in all negotiations and political initiatives is essential.

While the decree may result in the release of some individuals convicted of minor offenses, its societal impact is limited. Amnesty decrees like this one suffer from the absence of independent civilian or humanitarian oversight to verify implementation and accurately track beneficiaries. Additionally, the state’s reluctance to provide clear data on released detainees—beyond distributing the decree to official channels—exacerbates the persistent gap between legal text and practical enforcement. Syria’s crisis is not merely a legal or judicial issue; it reflects a deep-rooted political, economic, and social divide. The decree does not foster social cohesion, reconciliation, or a safe environment for the return of refugees and displaced persons.

Ultimately, this decree is not a genuine step toward resolving Syria’s crisis. It serves as a tactical maneuver to advance the regime’s interests, largely aimed at shaping public opinion, mitigating social discontent, and handling specific legal cases without addressing the underlying issue of thousands of detainees held since 2011. Its primary objective appears to be projecting a façade of reform to the international community, while offering little substantive change.

Appendix:

The following tables illustrate the articles excluded by Amnesty Decree No. 27 of 2024, with a comparison to Legislative Decree No. 24 of 2022.

First: Crimes excluded under the General Penal Code and its amendments:

| Article Number | Text / Description | Excluded in Legislative Decree No. 24 of 2022 | Excluded in Legislative Decree No. 27 of 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 271 | Espionage crimes. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 273 | Disclosure of confidential information, especially for the benefit of a foreign state. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 275 | Commercial or financial dealings with the enemy. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 276 | Participating in loans or facilitating financial operations for an enemy state. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 277 | Concealing or embezzling funds of an enemy state. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 341 | Bribery (accepting a gift or promise for performing a legal act within one’s role). | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 347 | Influence peddling (accepting undue payment to influence the conduct of authorities). | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 348 | A lawyer obtaining a judge’s favor through illegitimate means. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 349 | Embezzlement (embezzling funds entrusted to the employee). | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 351 | Exploiting one’s position (forcing someone to pay what is not owed). | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 361 | Abuse of authority (to obstruct the implementation of laws or judicial decisions). | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 386 | Removing or destroying official documents. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 387 | Destroying official records. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 398 | False testimony before judicial or administrative authorities. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 402 | Submitting a false report. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 403 | Providing a false translation. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 405 | False oath in civil cases. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 428 | Forging the state’s seal or using it for unlawful purposes. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 450 – 457 | Forgery in official documents. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 458 | Presenting a fake identity before public authorities. | ✘ | ✔︎ |

| 459 | Presenting a fake identity for someone to the authorities. | ✘ | ✔︎ |

| 460 | Forgery in private documents. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 473 – 478 | Crimes of adultery and incest. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 499 | Deceiving women and exploiting them with false promises. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 500 | Kidnapping for the purpose of marriage. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 504 | Deflowering under the pretext of marriage. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 507 | Disguising oneself to enter women-only spaces. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 517 | Offending public decency. | ✘ | ✔︎ |

| 518 | Offending public decency under Article 208. | ✘ | ✔︎ |

| 520 | Sexual intercourse against nature. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 576 | Arson by intent. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 579 | Causing a fire by negligence. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 580 | Removing or disabling firefighting equipment. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 584 | Damaging telecommunications equipment. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| 625 bis | Theft of cars or motorcycles. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

Second: Articles and Paragraphs Excluded Under the Military Penal Code:

| Article Number | Text / Description | Excluded in Legislative Decree No. 24 of 2022 | Excluded in Legislative Decree No. 27 of 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paragraphs (b, c, d) of Article 133 | b: Imprisonment from 1 to 3 years for any soldier who sells, pawns, or maliciously disposes of the weapon assigned to him. c: Imprisonment from 2 to 5 years for any soldier who steals a weapon belonging to the army. d: Imprisonment from 1 to 3 years for any soldier who steals, embezzles, sells, pawns, or breaches trust regarding funds, equipment, devices, clothing, ammunition, or animals belonging to the army | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| Article 134 | Punishment as stipulated in Article 133 for anyone not guilty of desertion but who fails to return army property in their possession. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| Article 140 | Punishment as stipulated in the Military Penal Code for anyone who incites desertion or facilitates it | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

Third: Other Laws and Articles Excluded from the Amnesty Decree:

| Law / Article Number | Description | Excluded in Legislative Decree No. 24 of 2022 | Excluded in Legislative Decree No. 27 of 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Legislative Decree No. 68 of 1953 | Prohibition of transporting goods from enemy countries. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| Law No. 286 of 1956 | Prohibition of dealings with Israel. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| Law No. 10 of 1961 | Criminalization of opening and managing brothels. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| Law No. 24 of 2006 | Licensing of exchange institutions. | ✘ | ✔︎ |

| Law No. 18 of 2010 | Telecommunications Law. | ✘ | ✔︎ |

| Legislative Decree No. 40 of 2012 | Building violations. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| Law No. 3 of 2013 | Economic Crimes Law. | ✘ | ✔︎ |

| Legislative Decree No. 35 of 2015 | Punishments for illegally drawing electricity from the public grid. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| Law No. 14 of 2015 | The old Internal Trade and Consumer Protection Law (abolished), but crimes committed under it remain applicable. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| Legislative Decree No. 8 of 2021 | Consumer protection and anti-monopoly. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| Law No. 20 of 2022 | Cybercrimes Law. | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| Law No. 7 of 2023 | The Law on the National Authority for Information Technology Services. | ✘ | ✔︎ |

| Law No. 42 of 2023 | Imposing penalties for acts disrupting the examination process. | ✘ | ✔︎ |

| Law No. 39 of 2023 | Forestry Law: the following articles: | ✘ | ✔︎ |

| Articles 44, 48, 49, 52, 54, 57, 58, 61, 62 | Punitive articles related to arson, transportation of raw materials, charcoal production from forest products, etc. | ✘ | ✔︎ |

| Article 55 | Violation of paragraphs /i-k-l/ of Article /4/ and paragraph /a/ of Article /6/. | ✘ | ✔︎ |

| Article 59 | Violation of Article /34/ related to reclamation of private forest land. | ✘ | ✔︎ |

| Legislative Decree No. 5 of 2024 | Prohibition of transactions in currencies other than the Syrian pound. | ✘ | ✔︎ |